⭐ Learn & research a topic

- English

- 中文

- 日本語

TL;DR

The purpose of visualizing notes is to gain a deep understanding of what you've learned. If all of your notes are very long and you don't break down the knowledge into smaller parts, the understanding you can gain from visualization will be very limited. Real deep understanding doesn't come from the "relationship between two books" but from the "relationship between all the concepts in these two books."

You can only gain a deep understanding of the topics you care about through visual note-taking when you atomize your notes. Atomic note-taking does not mean you cannot have long notes. It means that each concept card should only contain one concept and be supported by its content. To ensure clarity, you should always describe the concept in one sentence and use that sentence as the title of the concept card.

Foreword

I read a lot. For me, the most frustrating issue with reading is that great books often contain a high volume of content that is not easy to fully digest and integrate with my existing knowledge. Even when I fully digest the content, I often find it difficult to recall knowledge that I learned in the past purely from memory, which makes it hard to apply what I've learned to my current work.

I have met many people who face the same problem in learning, and this issue is what many note-taking (a.k.a. knowledge management) tools are trying to solve. Unfortunately, most of these tools put too much focus on how you store your notes (e.g., folders, graphs, relational databases, etc.) and neglect important aspects of learning such as acquisition (making sense of knowledge), retention (recalling past knowledge), and application (applying knowledge in a real-world scenario).

In this article, I will share a real-world example of how I developed an effective method for acquiring, retaining, and applying knowledge using Heptabase, a tool my team and I created for learning and research. While this is not the only workflow for learning, it has worked extremely well for me, and I believe almost anyone can apply it to their learning.

Method Overview

The famous Feynman learning technique suggests that the best way to develop a deep understanding of a topic is to teach it to a child. I would say that whenever you want to teach something, you need to first figure out the structure of the knowledge and be able to articulate that structure clearly. The method that I developed can help you achieve that with five steps:

- Highlight all important paragraphs while reading.

- Dissect the content of a book into granular concepts.

- Map the relationships between these concepts.

- Group similar concepts together.

- Integrate these newly learned concepts with previously known concepts.

Here's a screencast of how I conduct this process. This screencast is not staged. It's a real example of how I develop an understanding of a book I read called Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. You don't need to watch it fully (it's 4 hours long!), but quickly skimming through different parts of the video will give you a clear sense of how I extract core concepts from the book and develop my understanding of it. If you want to explore and play with the whiteboard I created in the video, here’s the link to it.

[2024/01/03 Update] I have created a tutorial showing and explaning how I conducted the five-step process in action using Heptabase. I highly recommend you check it out!

Step 1: Highlight all important paragraphs while reading.

The first step in the process is to highlight important paragraphs from the book you have read and organize them by chapter.

Depending on the reader you use, the highlighting process may vary. If you are using a desktop reader, you can simply copy and paste the text into a Heptabase card. If you are using a Kindle or iPad reader, you can export all the highlights of the book into a Markdown file and then import it into Heptabase as a card. If you are reading a physical book, you can take notes in Heptabase whenever you finish reading a chapter.

It doesn't matter which tool you use to create highlights, as long as your output is one large card for the book that includes your highlights from different chapters.

Step 2: Dissect the content of a book into granular concepts.

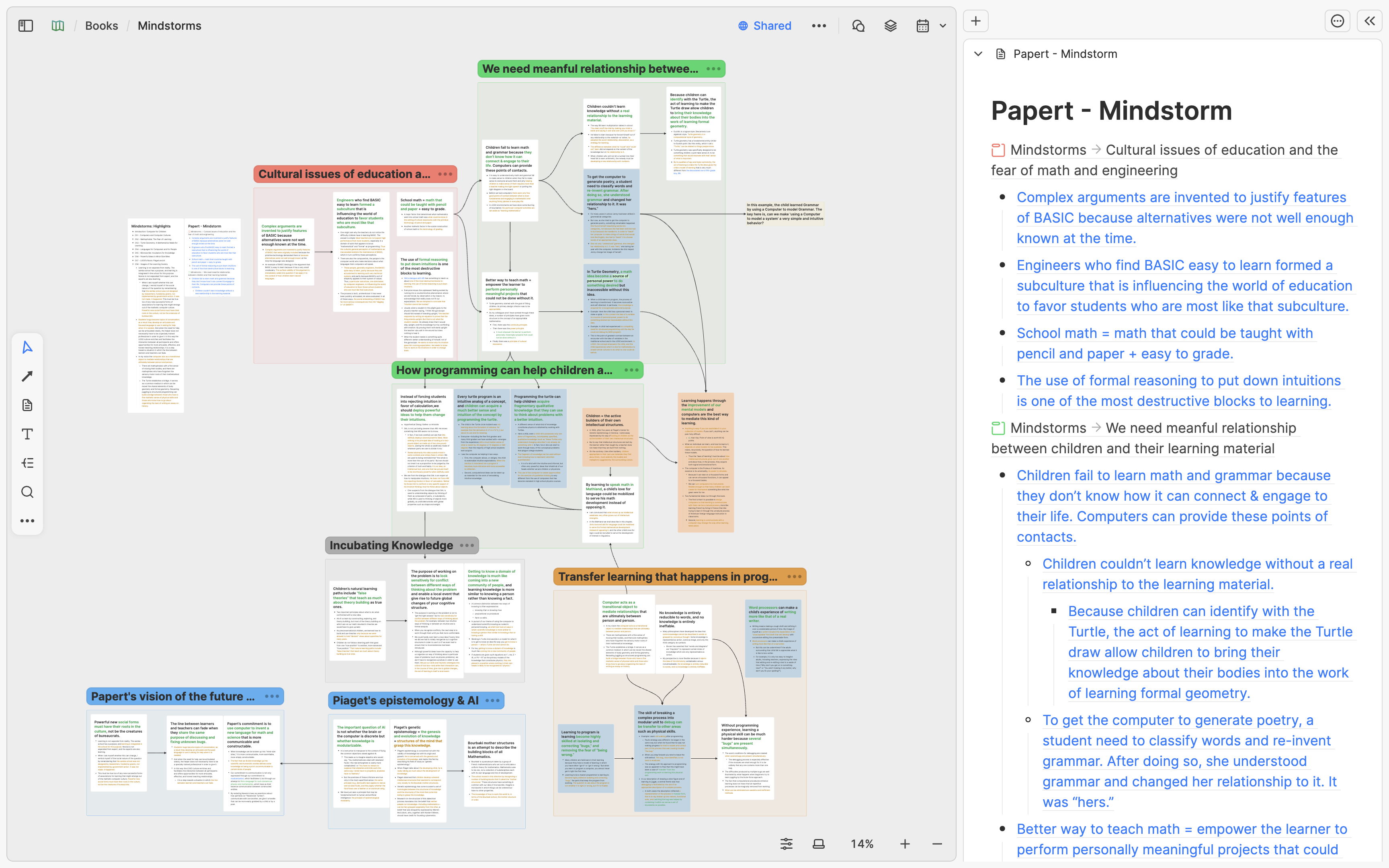

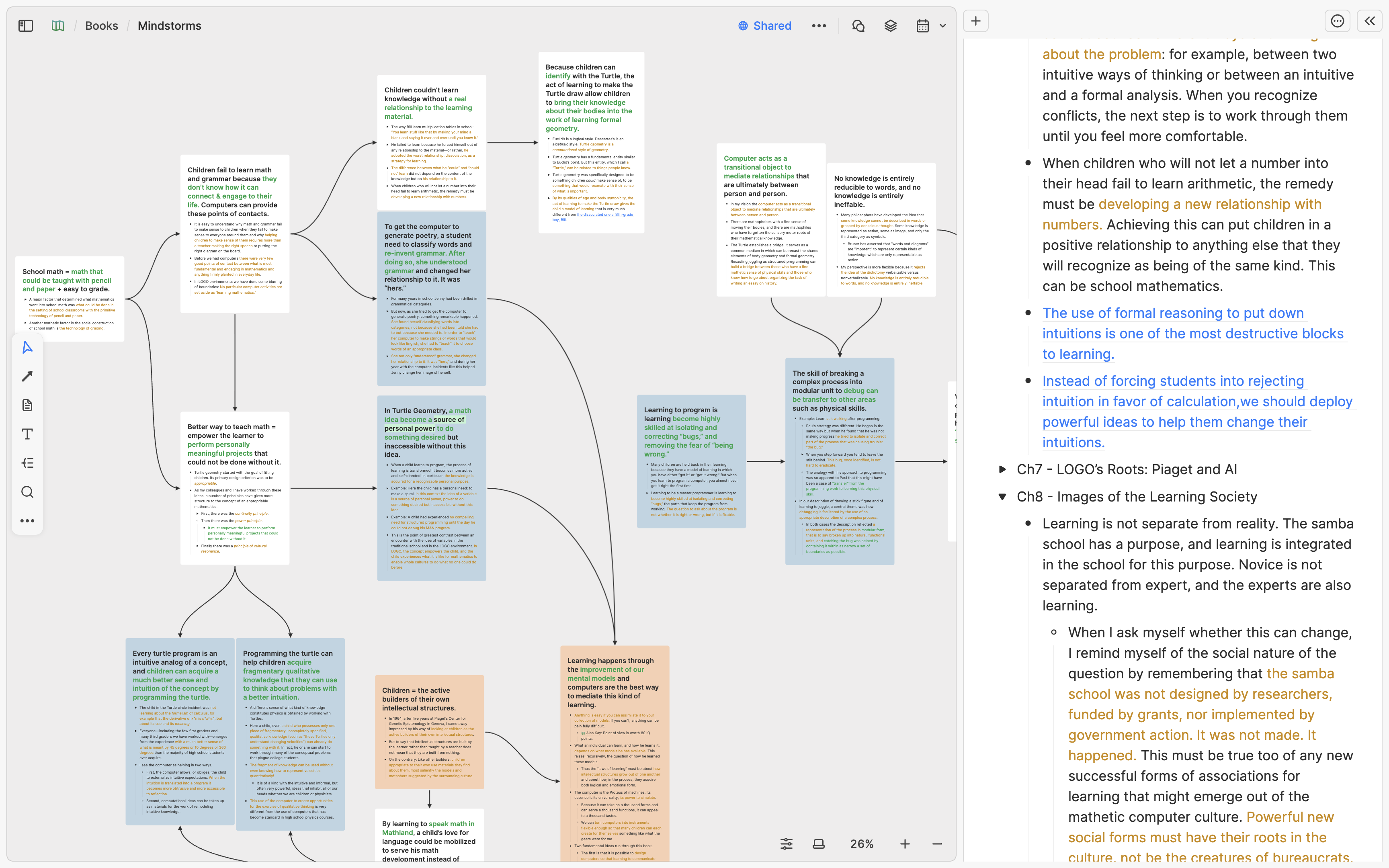

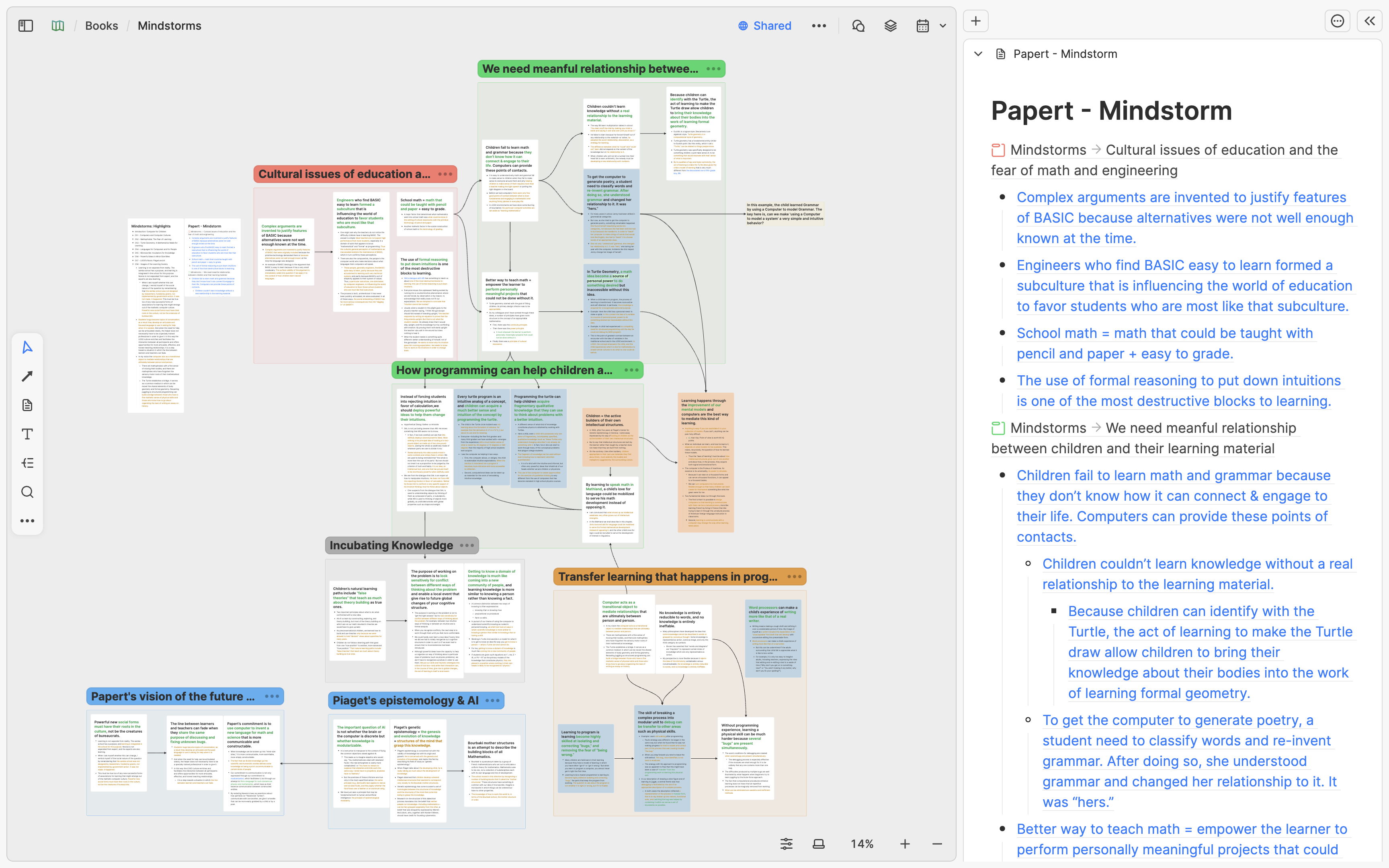

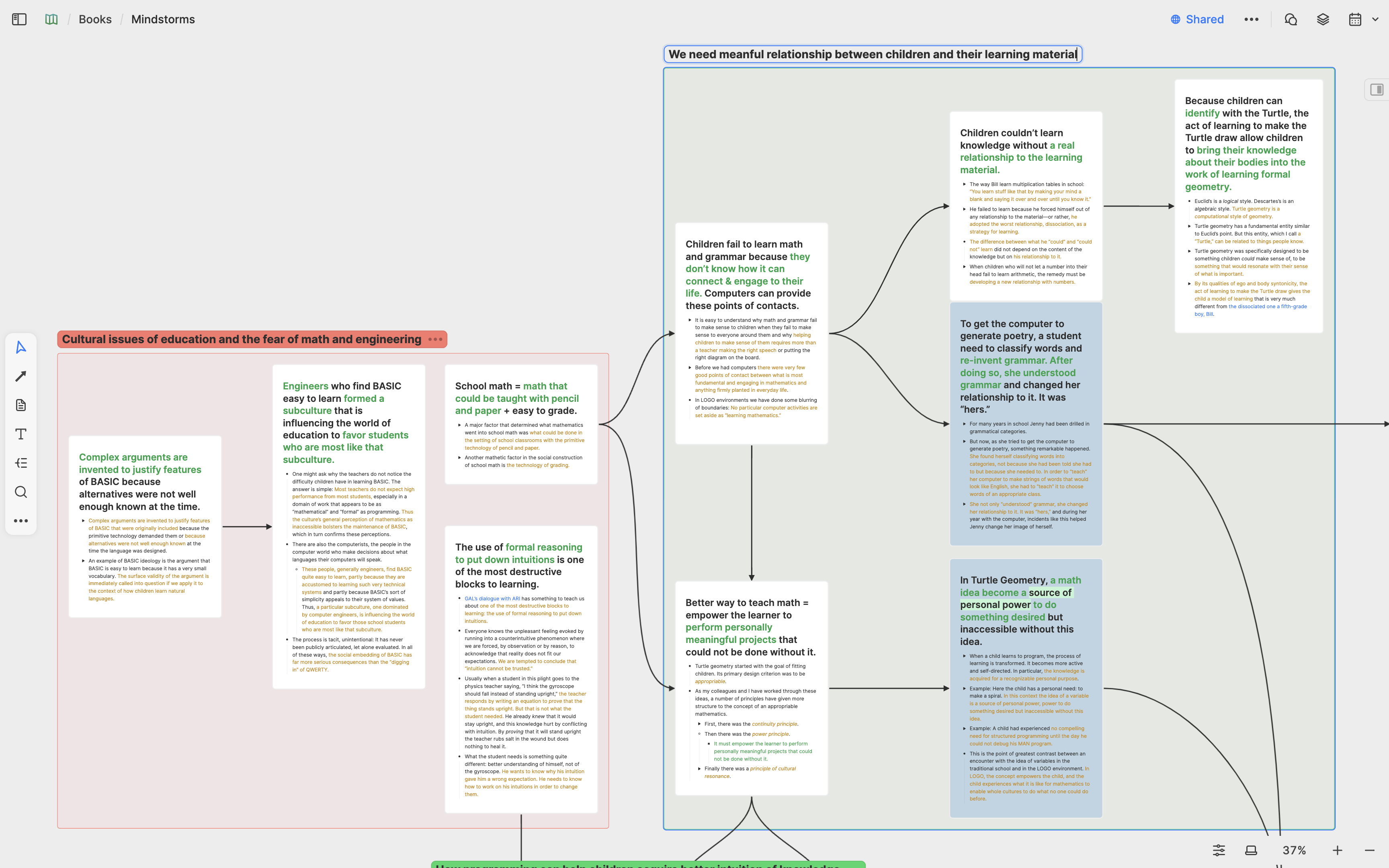

Once you have the book card ready, you can create a whiteboard and add that card through the import panel of the card library. In my example, I created a sub-whiteboard named Mindstorm under the parent whiteboard Reading Notes, and dragged my Mindstorms book card onto this sub-whiteboard.

Once I have the card ready, I open it on the right split panel so I can better see its content. I usually start by skimming through all the content to identify key concepts. When I decide that there's a concept I want to extract, I select the related blocks and drag them out onto the whiteboard to create a new card.

Simply creating a concept card is not enough. To ensure clarity, I always describe the concept in one sentence and use that sentence as the title of the concept card. Then, I reorganize the content of the card into a structure that makes sense to me, and perhaps even drag other related blocks from the original book card into this concept card.

Step 3: Map the relationships between these concepts.

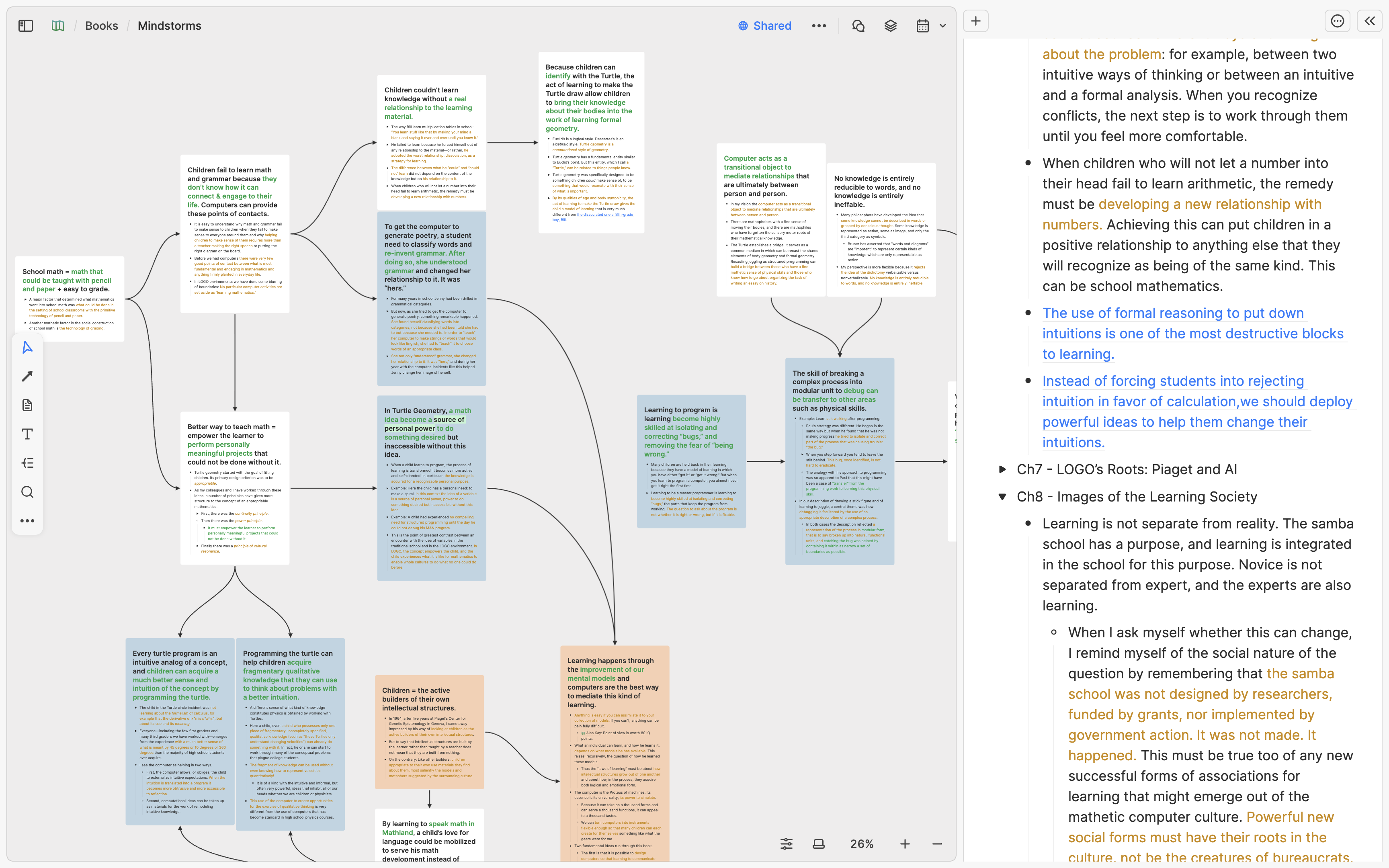

As I extract more concept cards from the original book card, I gradually add connections between them, or place similar concept cards next to each other. If I notice two concept cards are about the same idea, I merge them into one. At other times, I might break down a large concept card into several smaller ones to ensure granularity.

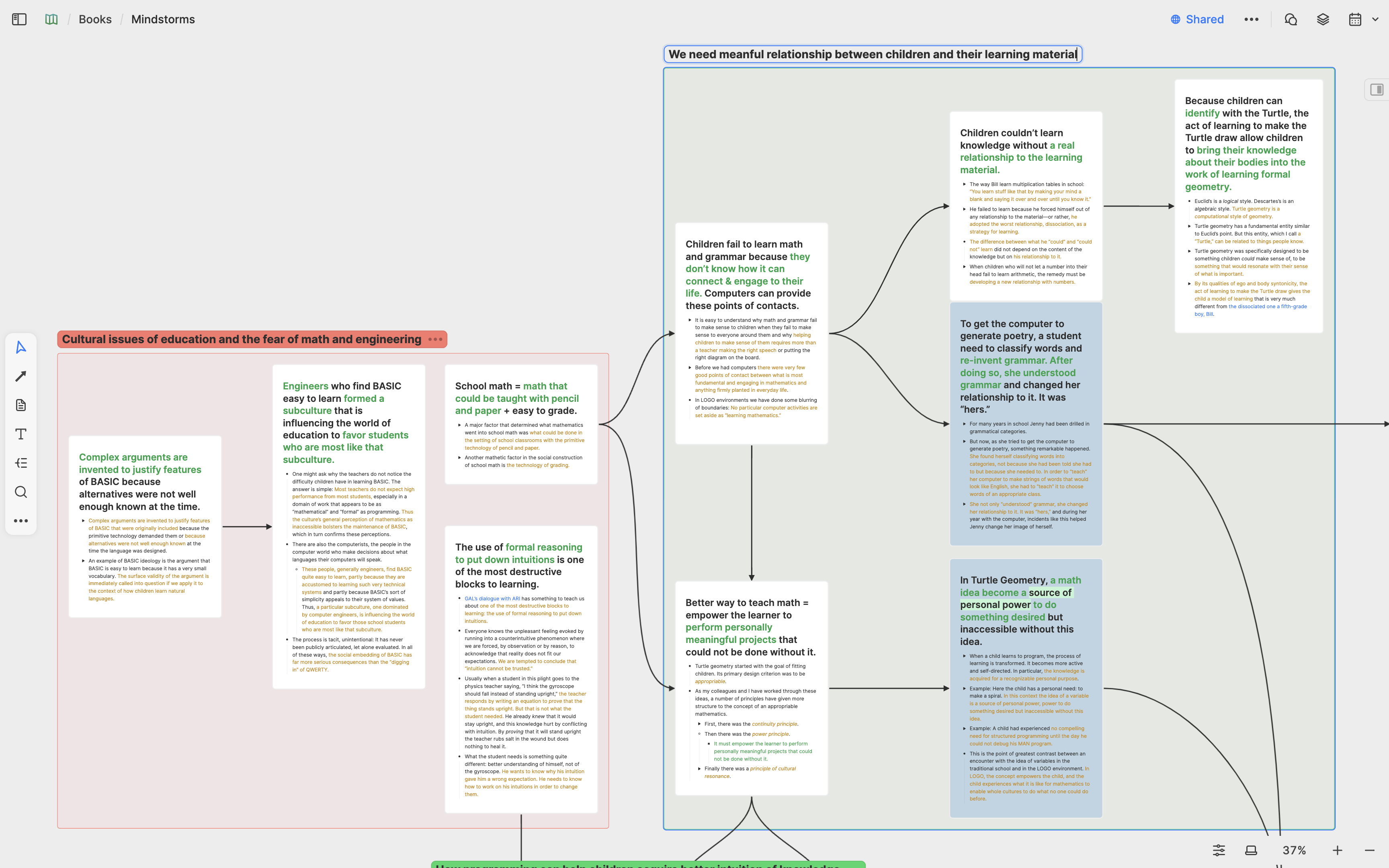

Step 4: Group similar concepts together.

After extracting all the content from the original book cards into concept cards, I close the split panel and start working on mapping and grouping relationships. Often, I find multiple concept cards related to the same sub-topic. In such cases, I group those concept cards into a section and add a name to that section. Naming the section should be done as carefully as naming a concept card because these are the things that you recall first when you revisit this whiteboard in the future.

Completing steps two through four typically takes anywhere from an hour to a full day, depending on the length and depth of the book. Once you've produced the final whiteboard, the knowledge acquisition phase is complete. In this process, what's truly valuable is not the final whiteboard you produce, but the thought process you invest while establishing the knowledge structure and titling each concept card and section during steps two through four. Deep understanding and insights often come from the process of deconstructing, reassembling, and describing knowledge in your own words. Only after going through this process does the knowledge truly become your own.

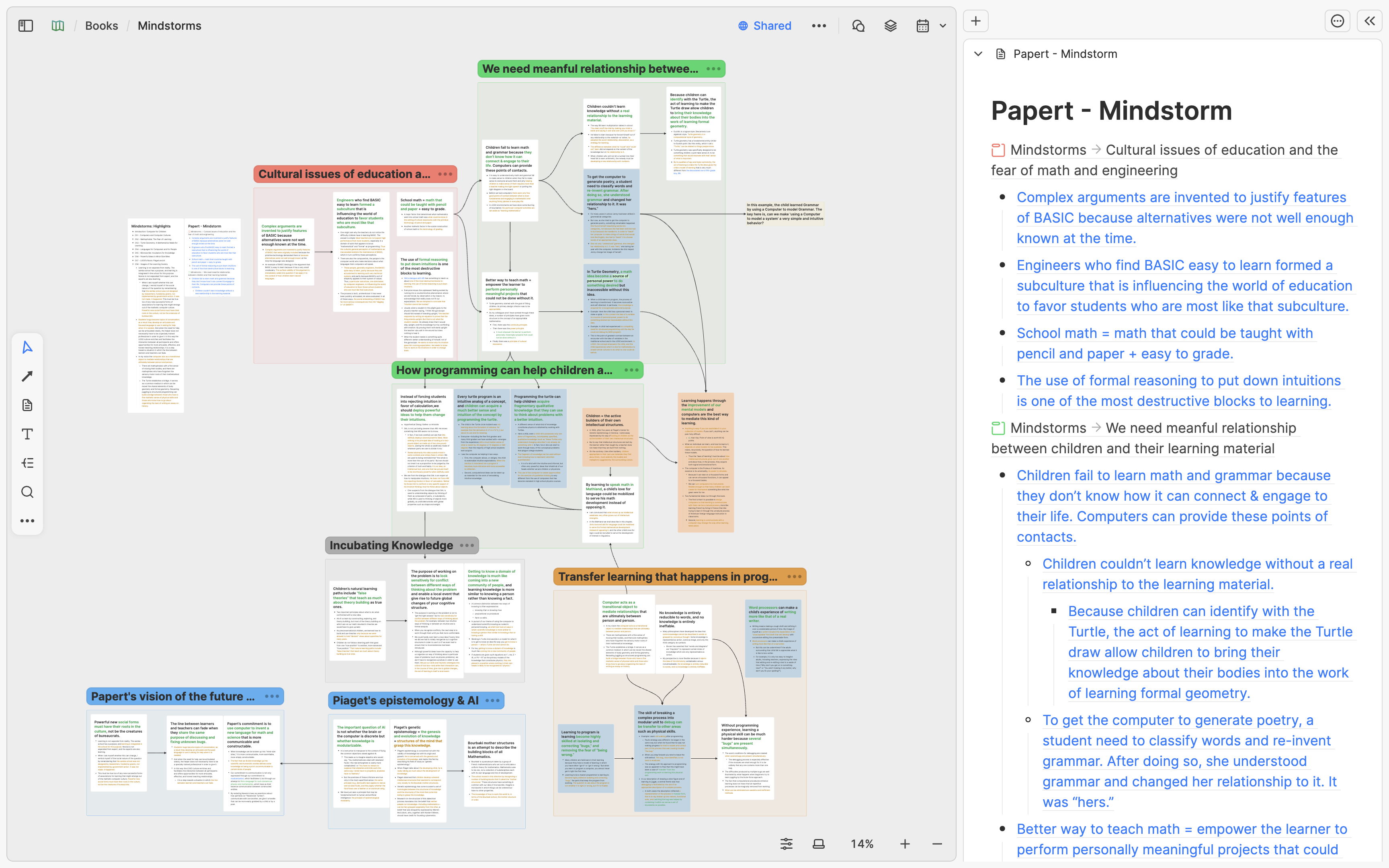

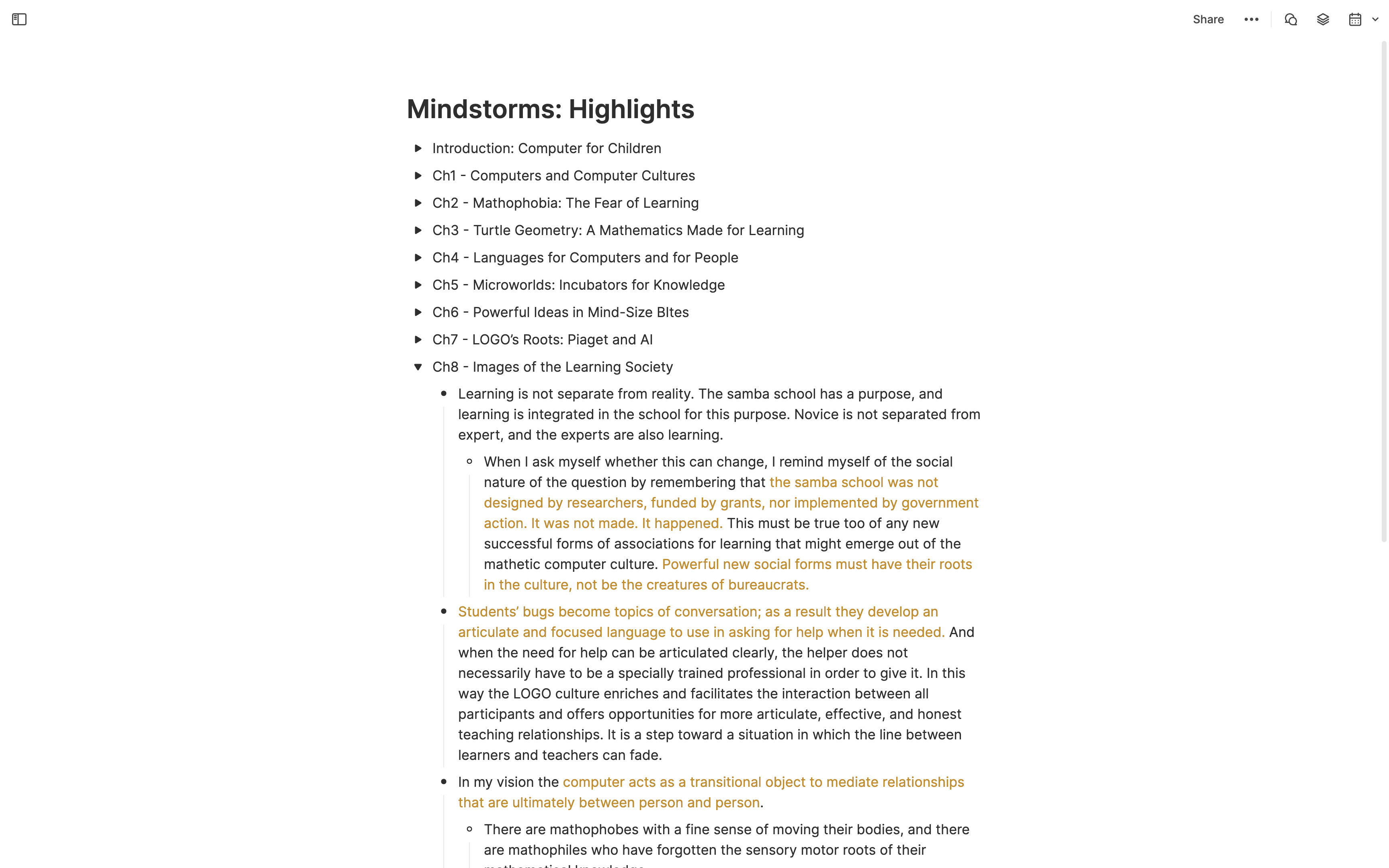

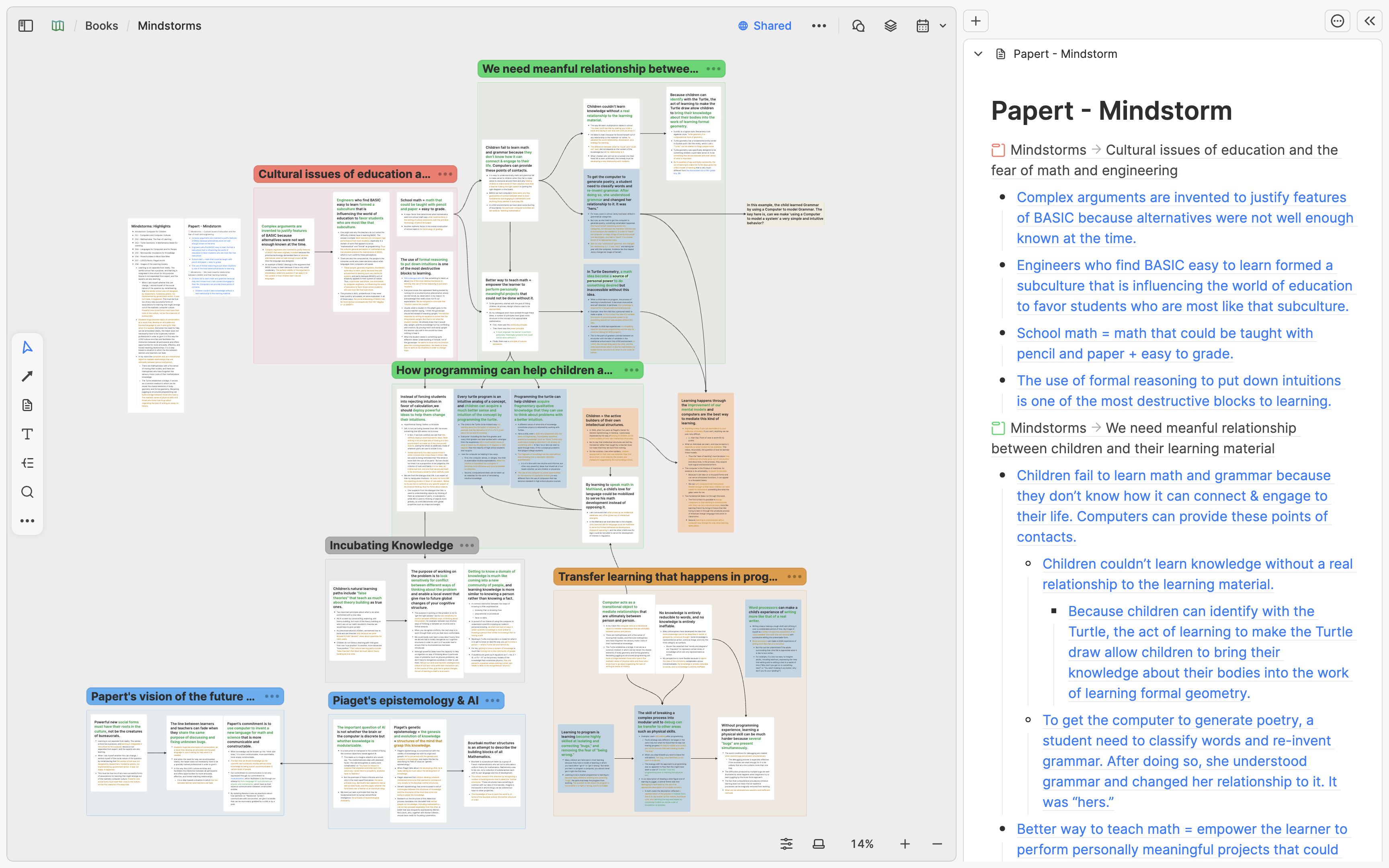

After completing the final whiteboard layout (including all arrows and sections), I will open the original book card in the right split panel of the whiteboard and re-paste the links to all the concept cards and sections back onto this book card. In the figure below, you can see that each link in this book card displays the title of a concept card. This is why, in the second step, I summarize each concept card in one sentence and use that sentence as its title. Only by doing so can I see the core concepts of this book without having to open the links of these concept cards when reading the book card.

For example, if I name a concept card's title as "Engineers’ subculture," looking back a few months later, it would be hard for me to recall what this card is specifically about. But if I name the title of this concept card as "Engineers who find BASIC easy to learn formed a subculture that is influencing the world of education to favor students who are most like that subculture," even without reading the content, I can recall the core concept in the future just by its title.

Step 5: Integrate these newly learned concepts with previously known concepts

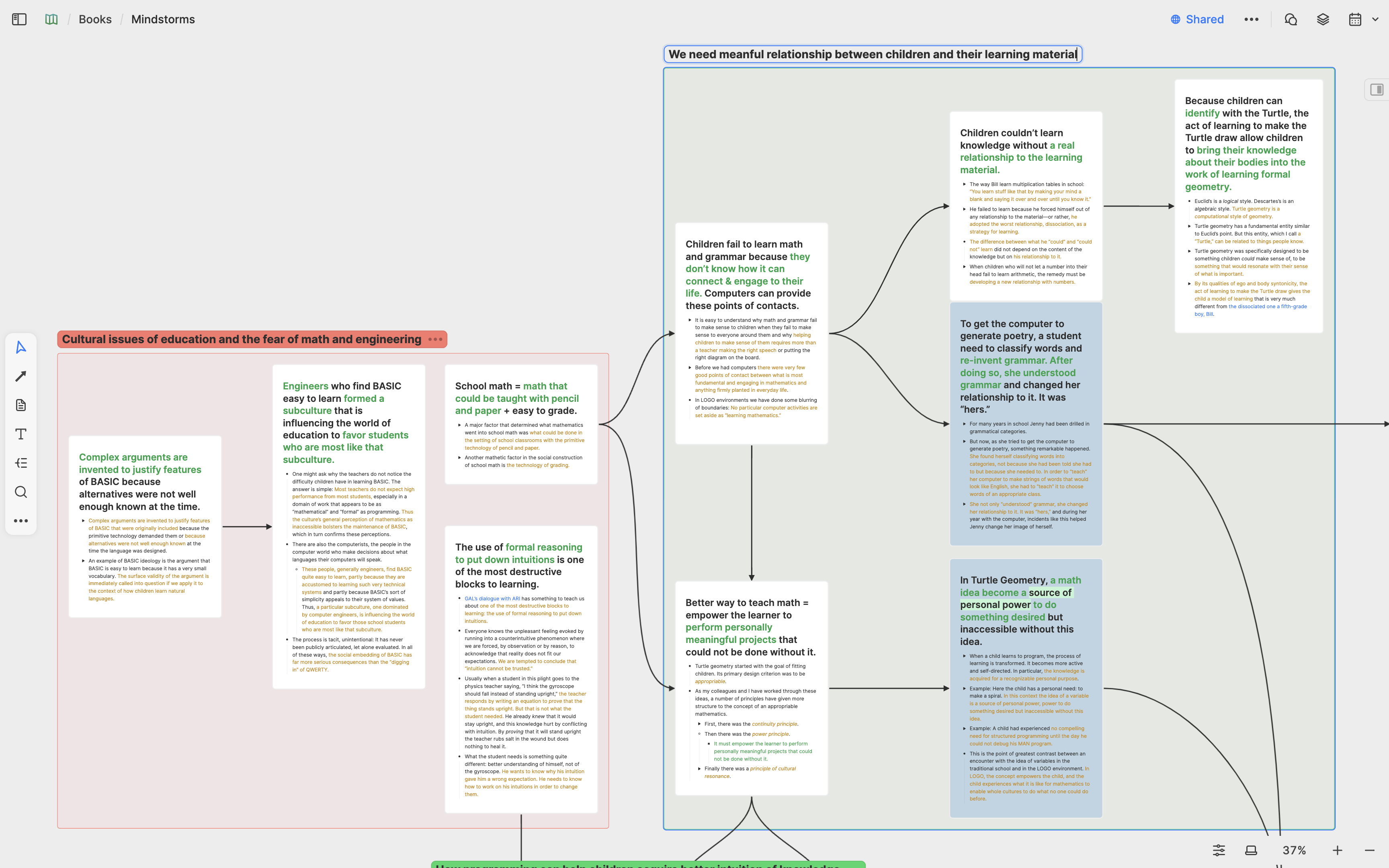

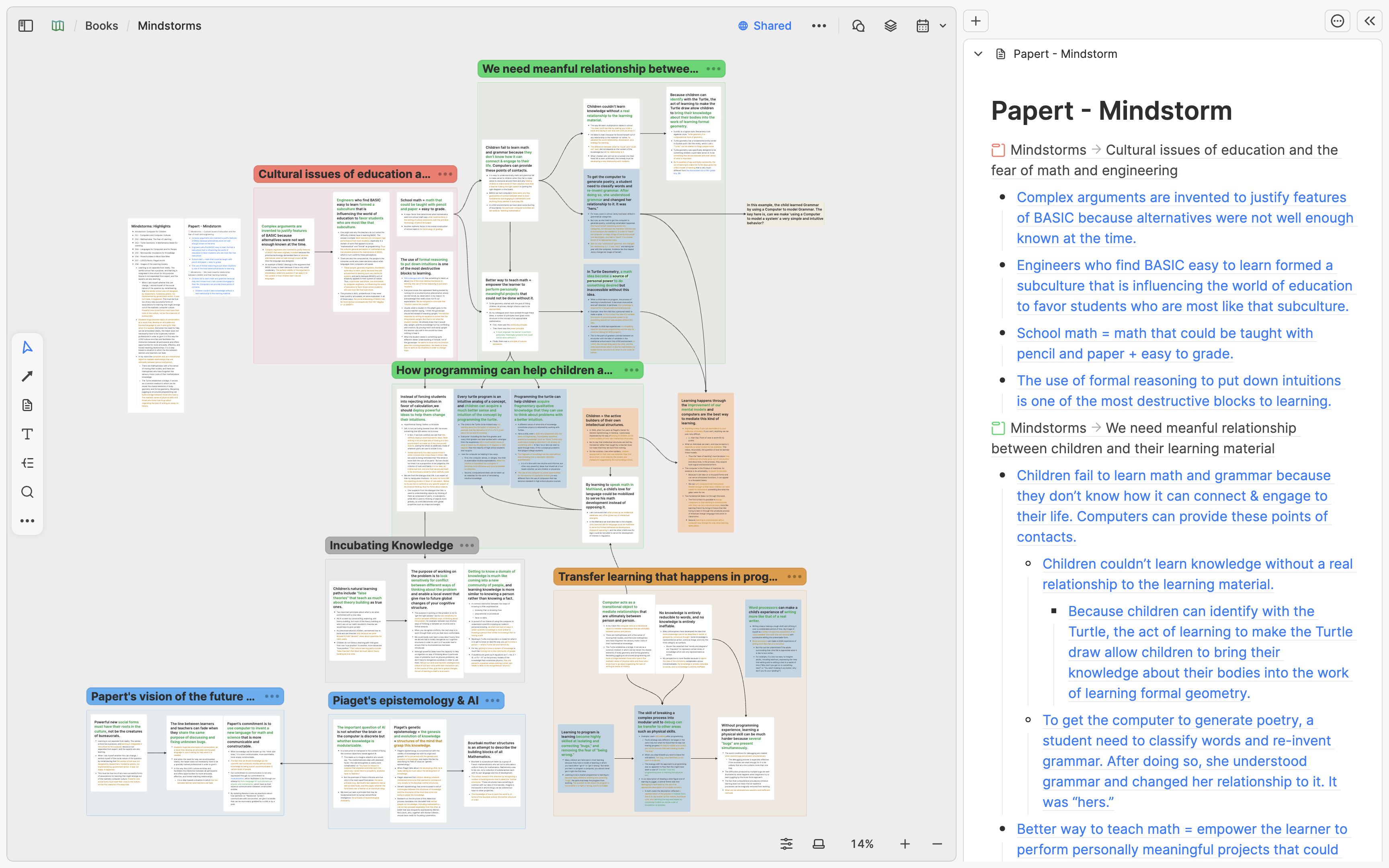

Up to now, I have gained a deep understanding of the core concepts of the book Mindstorms by breaking down and connect its core concepts on a whiteboard. But just understanding this book is not enough; I also want to truly integrate all the knowledge I have learned in the past, present, and future. In other words, I want to integrate the concept cards of this book with the concept cards I wrote for other books and lectures in the past.

Before doing this, I want to share an important learning mindset: You can only gain a deep understanding of the topics you care about through visual note-taking when you atomize your notes.

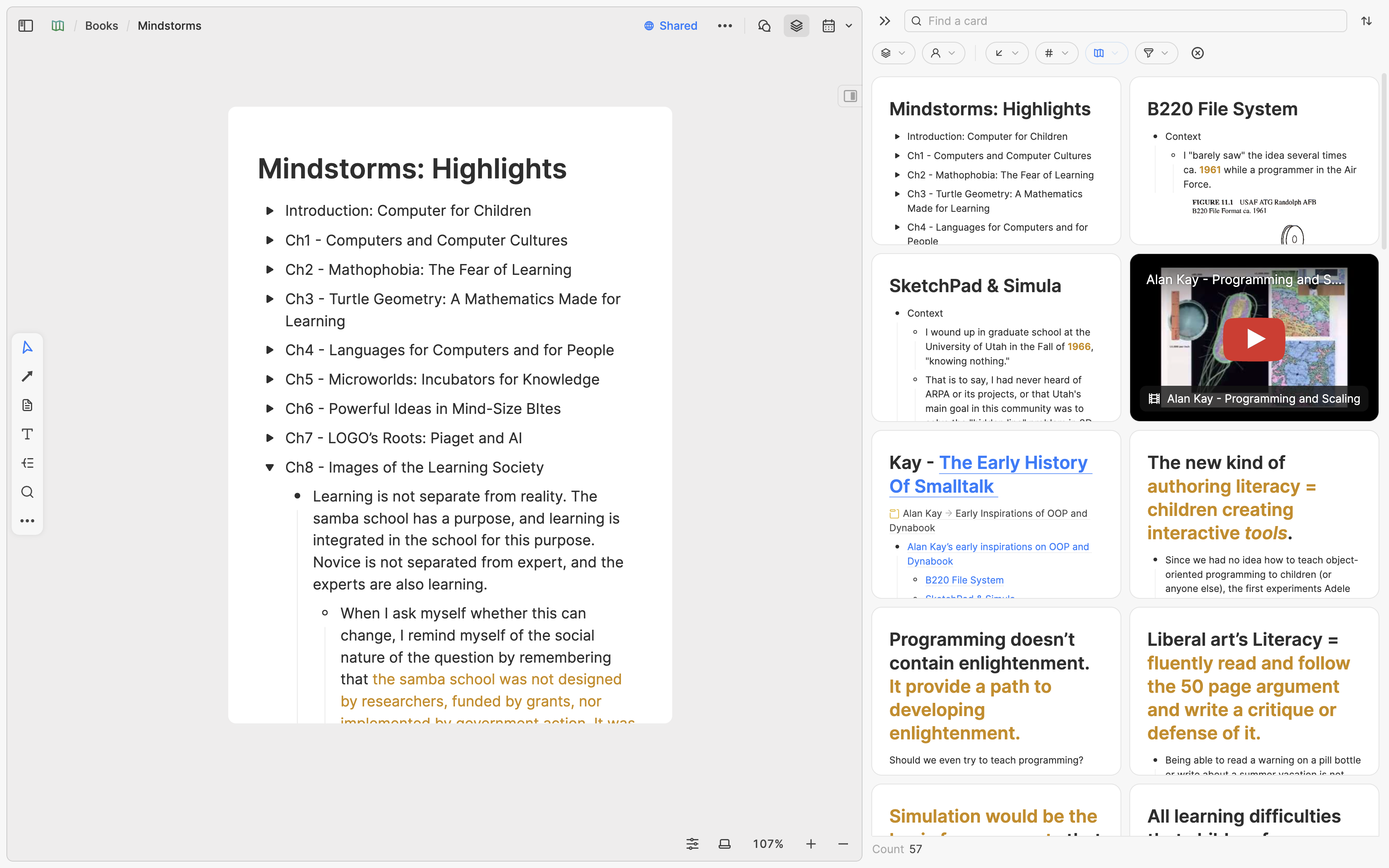

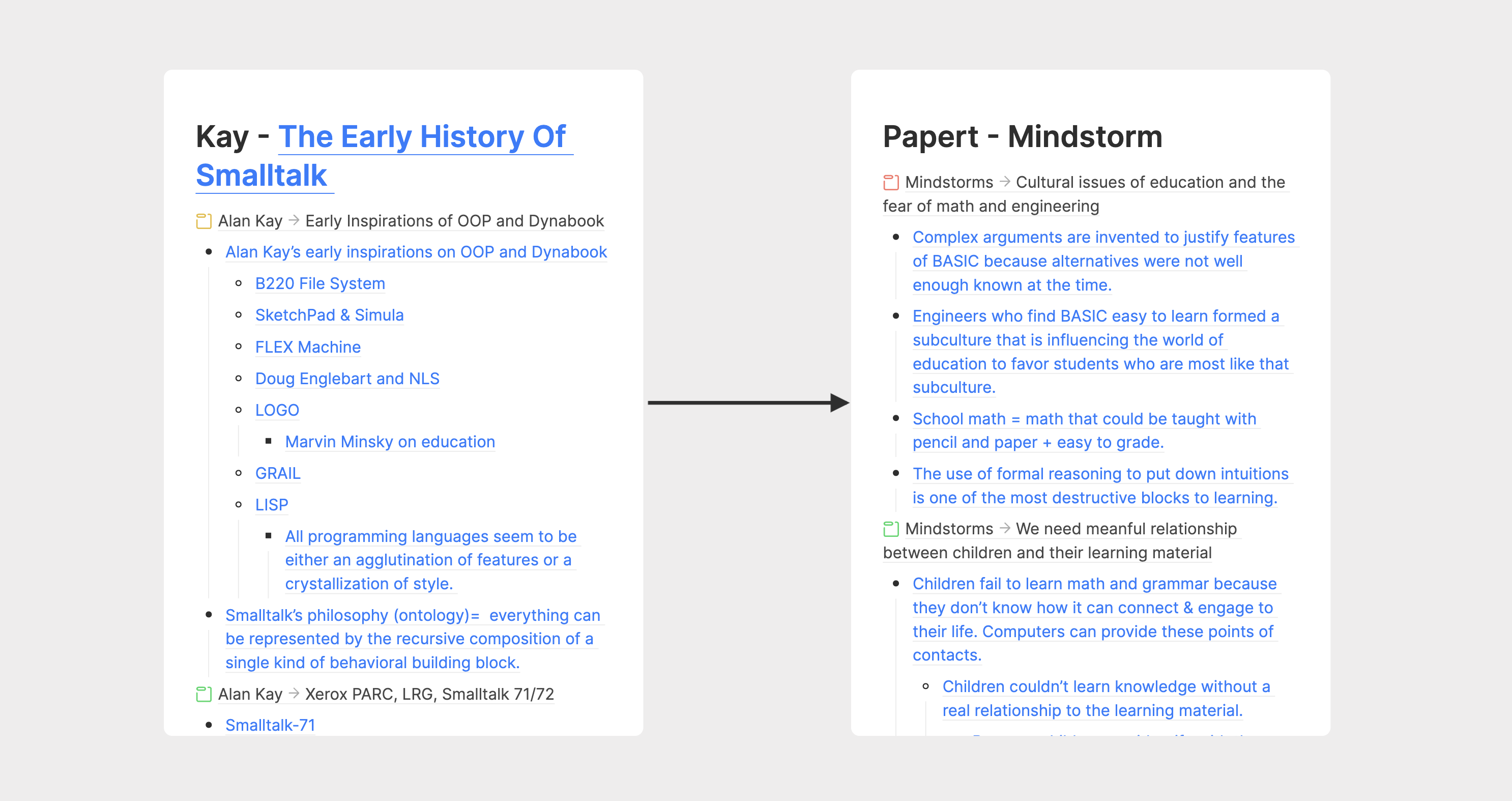

Many people, when first using a visual note-taking app like Heptabase, continue to use the old way of note-taking and write one note for each book or lecture, resulting in very long notes that contain many concepts. When your notes are in this format, it's hard to gain value from visualization.

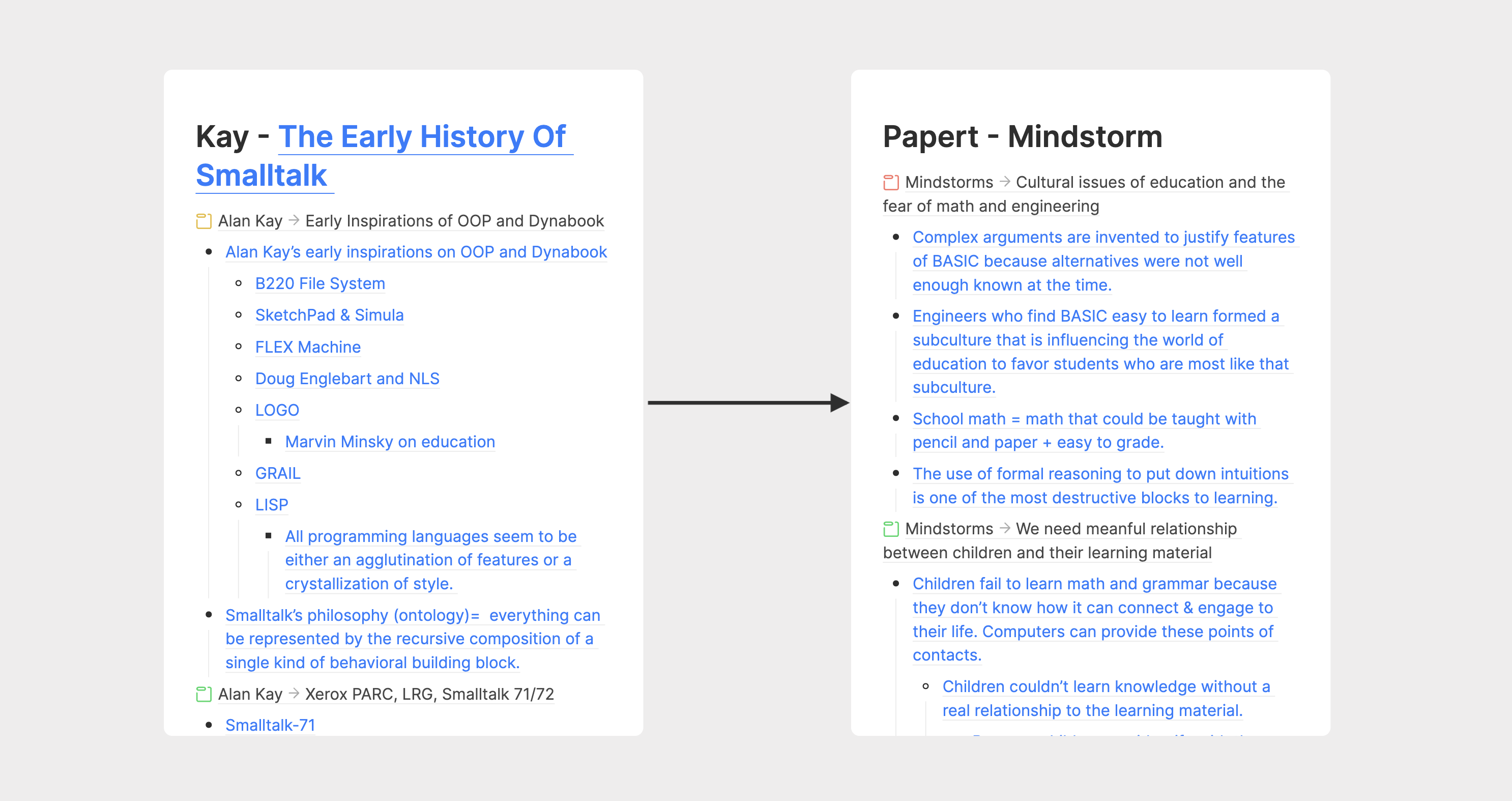

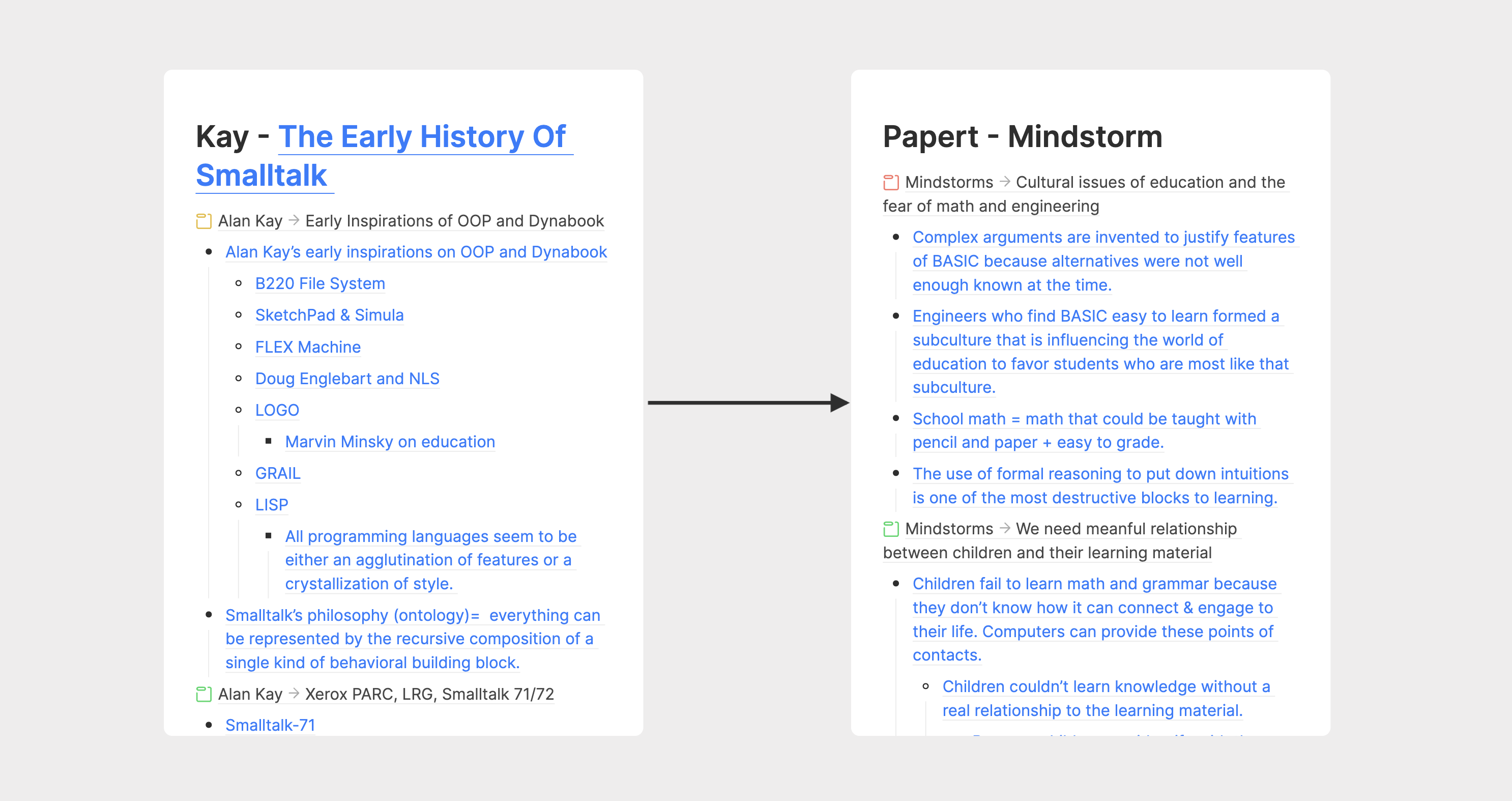

For instance, in the figure below, there are two book cards, each with a lot of content. Although the content of these two books is related, connecting these two book cards on a whiteboard does not provide any new value, as it is almost the same as putting them in the same folder.

The purpose of visualizing notes is to gain a deep understanding of what you've learned. If all of your notes are very long and you don't break down the knowledge into smaller parts, the understanding you can gain from visualization will be very limited. Real deep understanding doesn't come from the "relationship between two books" but from the "relationship between all the concepts in these two books." What you want to connect are not book cards, but individual concept cards that you extract from these books using the previous four steps.

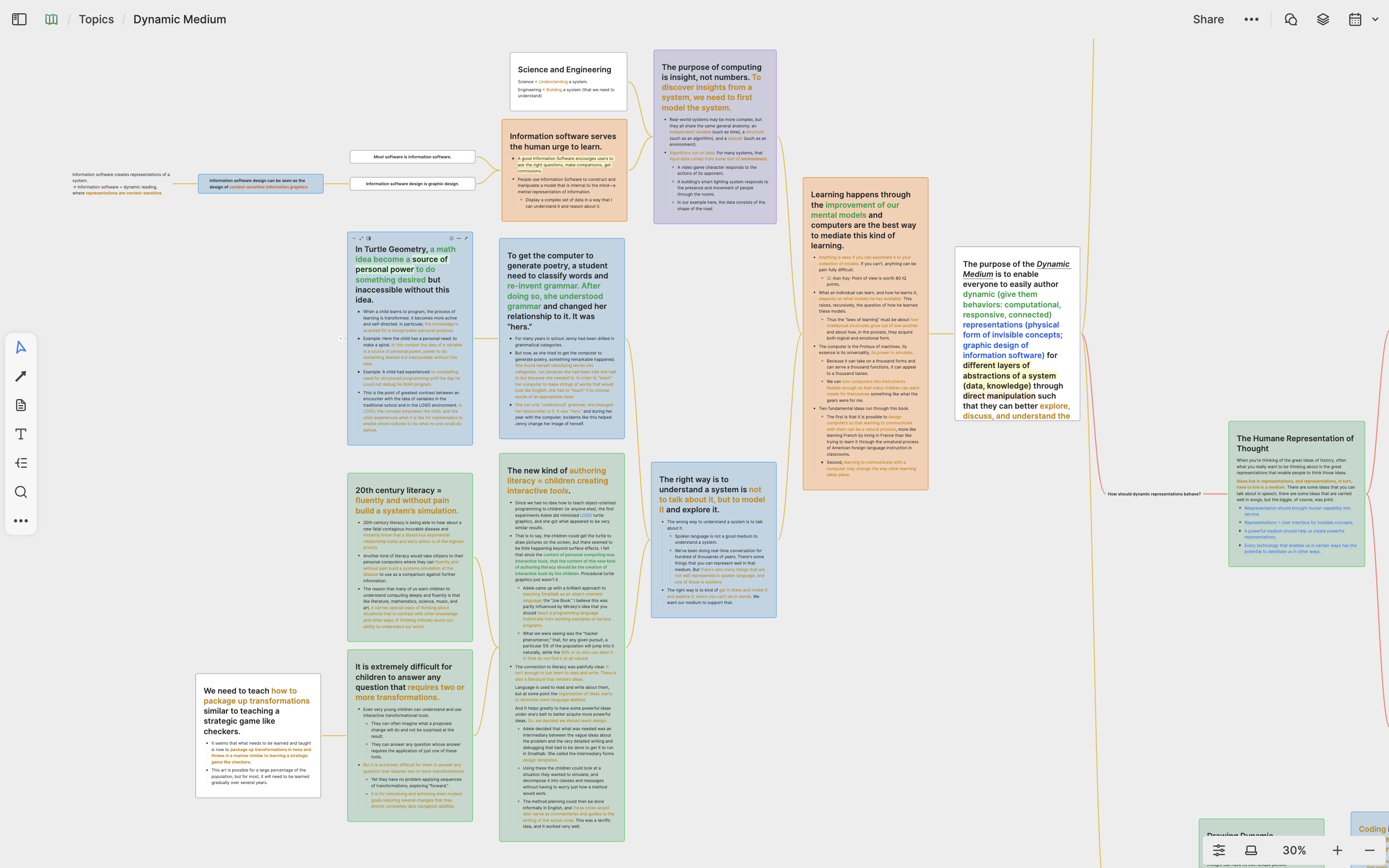

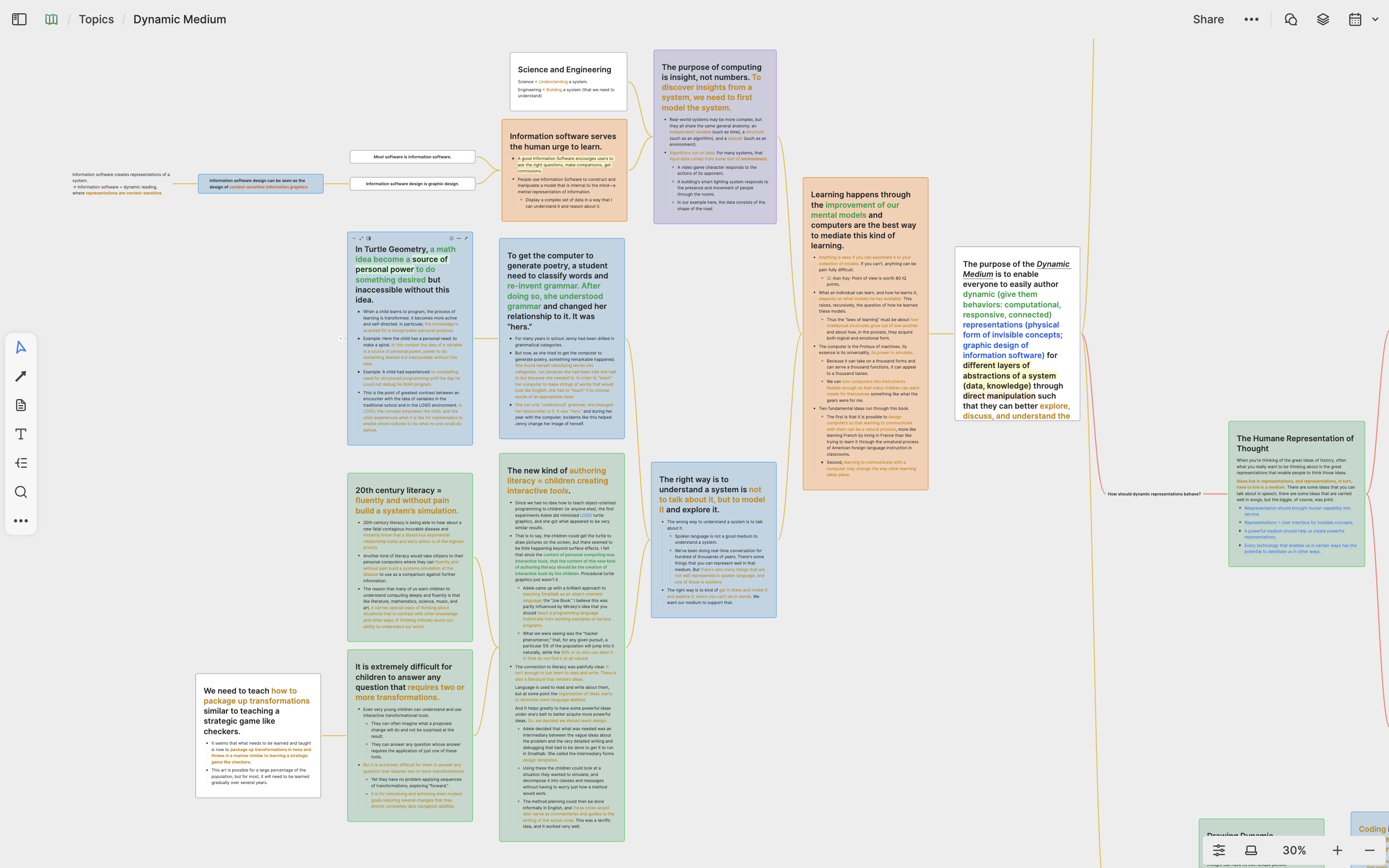

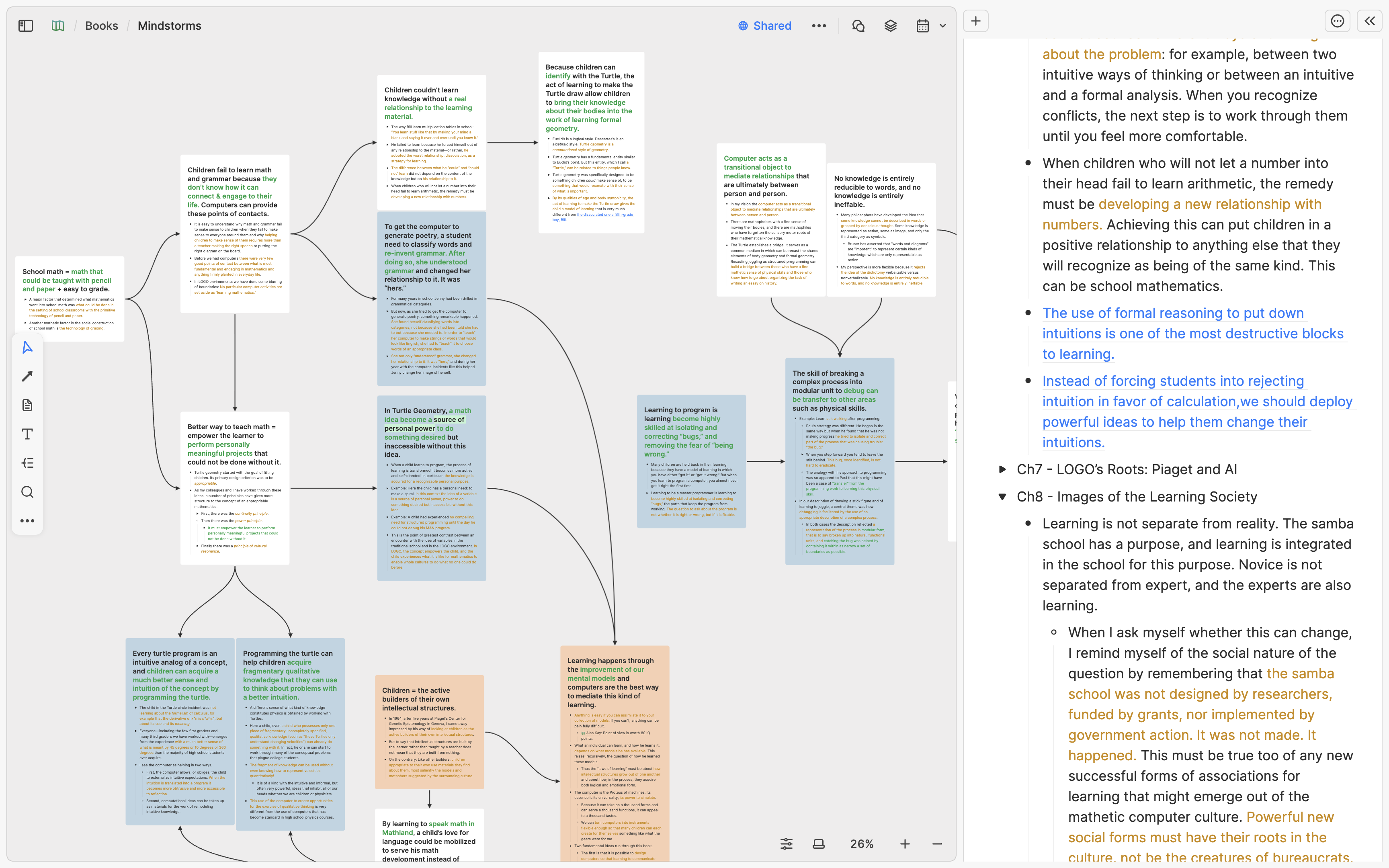

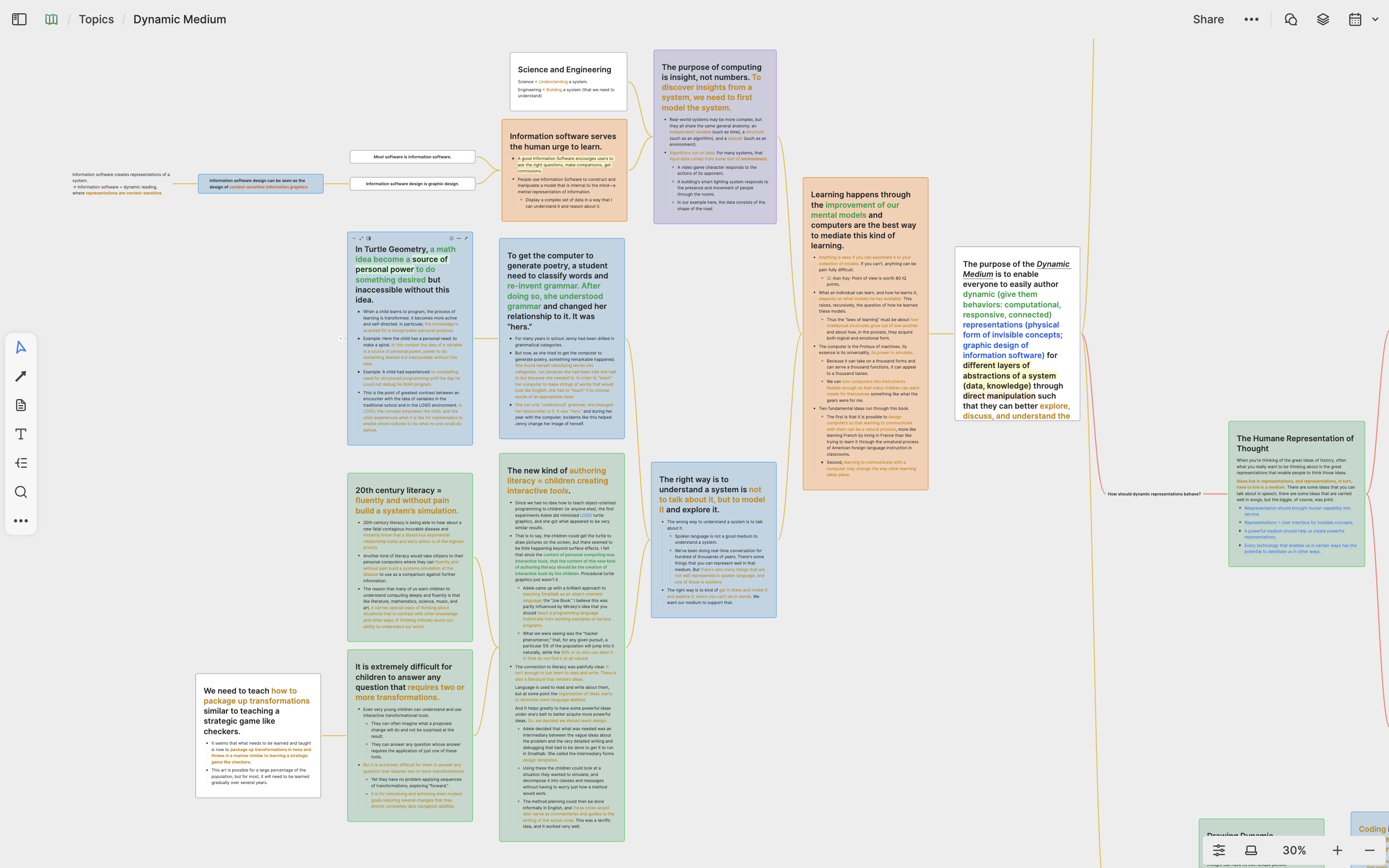

For instance, I've recently been researching how to design a computer-driven dynamic medium, and both books Mindstorms and The Early History of Smalltalk are highly relevant to this research topic. To better conduct this research, I created a whiteboard called Dynamic Medium and reused concept cards related to Dynamic Medium from these two books, organizing them using a mindmap to establish a unique understanding framework.

It's because I extracted and atomized the most important knowledge and ideas from these two books into reusable concept cards in the past when I read them, so that I can now easily apply my previous learning to new research topics. My past knowledge no longer sits uselessly in folders, but instead becomes the foundation for my newest research work!

Note: Atomic note-taking does not mean you cannot have long notes. It means that each concept card should only contain one concept and be supported by its content. If the content is long but all of it can be used to support the concept in the title, then the card is still an atomic concept card.

How to Learn and Research

After sharing how I implement the learning methodology in Heptabase, I would like to summarize the core ideas that underlie this methodology:

- I believe that the essence of learning and research is to break down and extract the important concepts from books, literature, lectures, and experiences. Then, one should connect, understand, and internalize these concepts in one's own way to build a deep understanding of what is known and unknown to humans.

- I believe all work plans and research papers are simply products of transforming this deep understanding into executable and communicable forms.

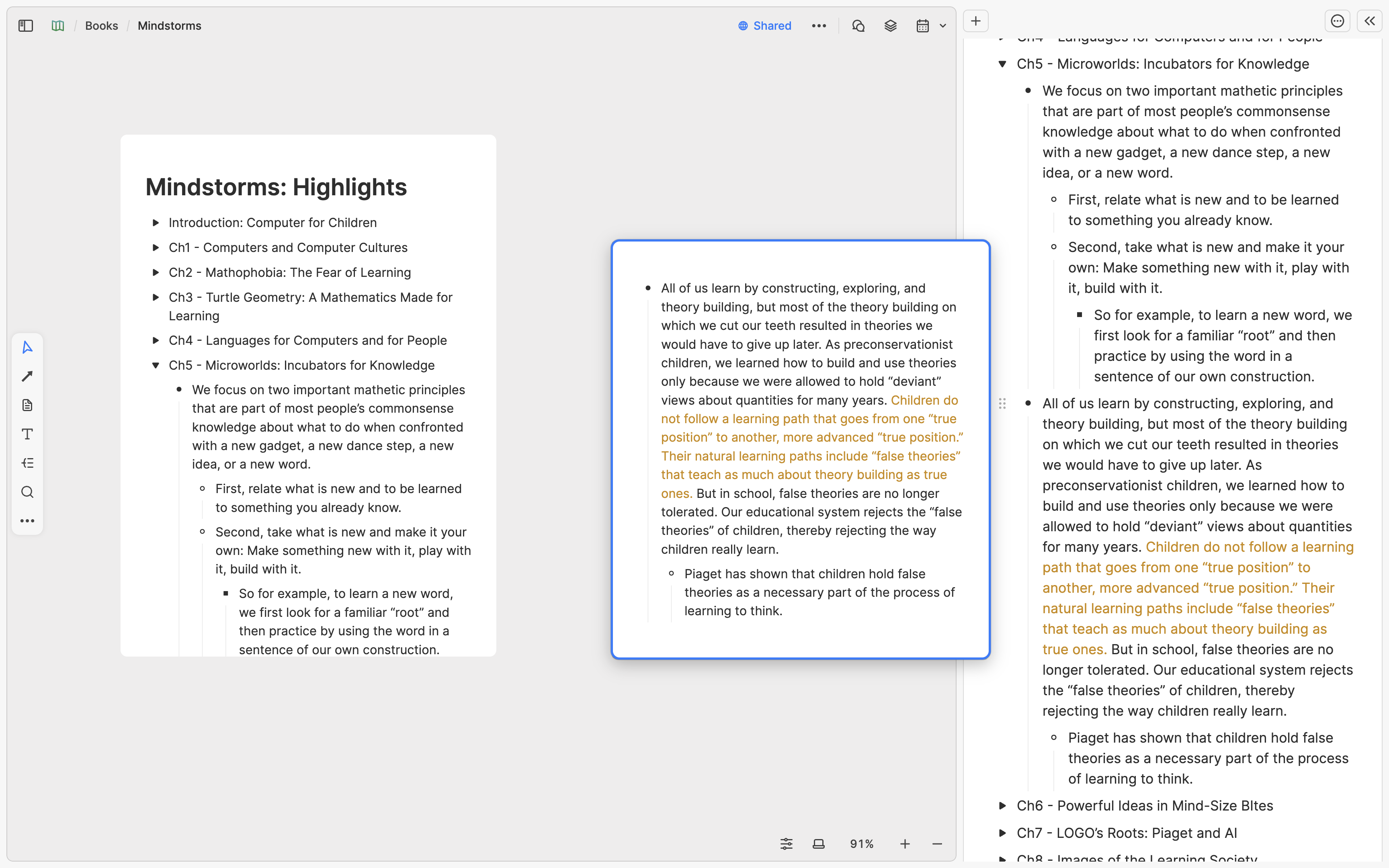

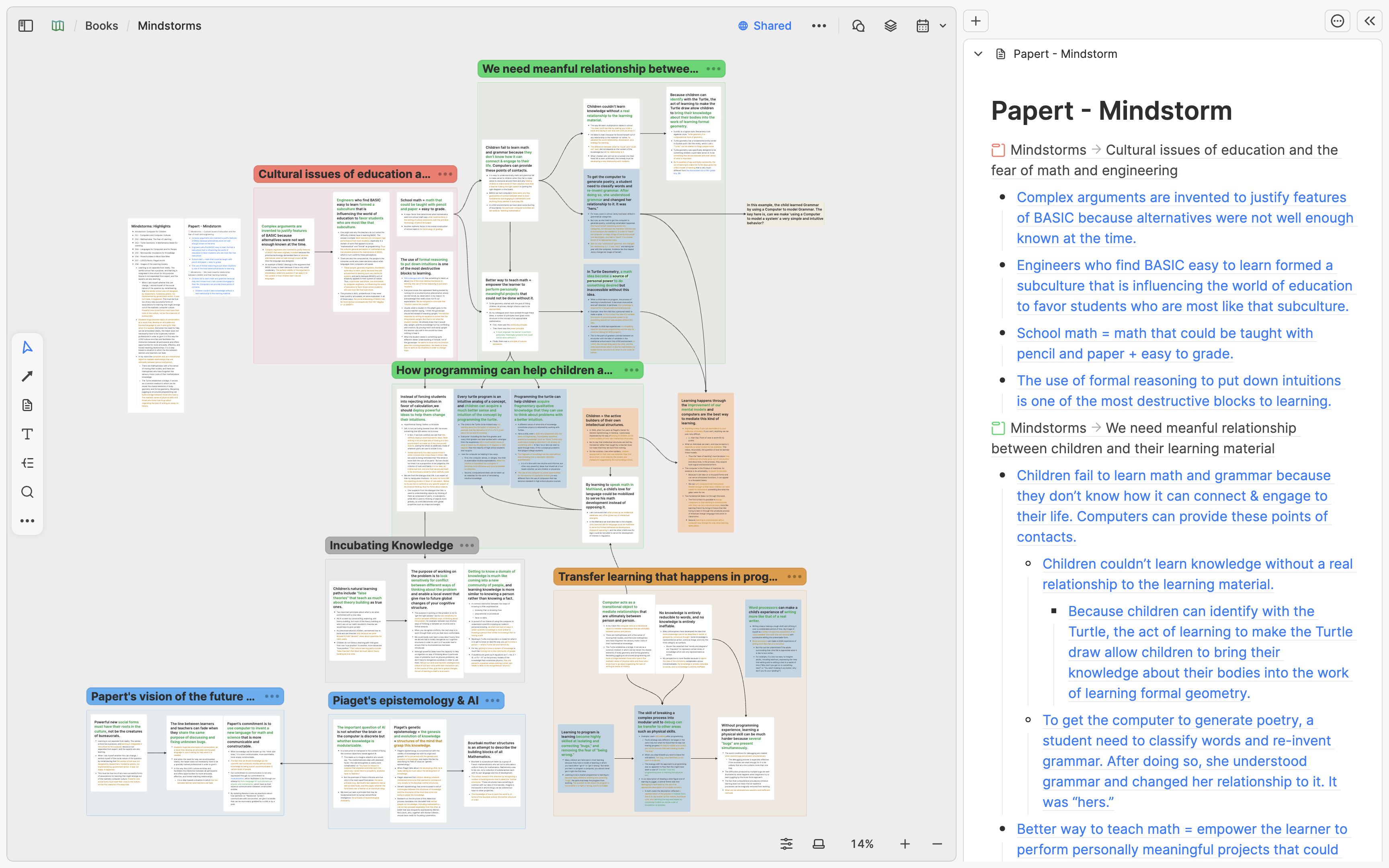

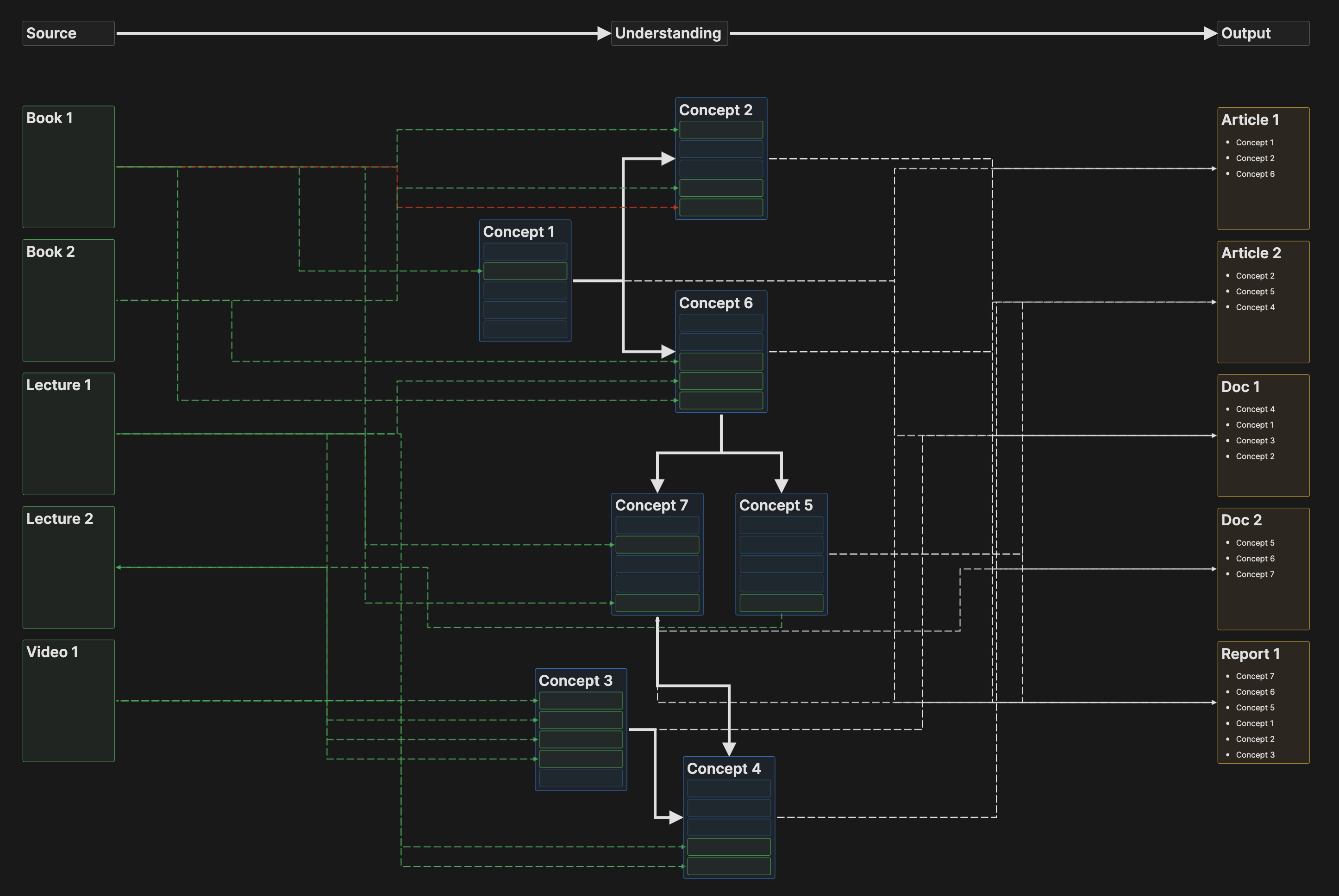

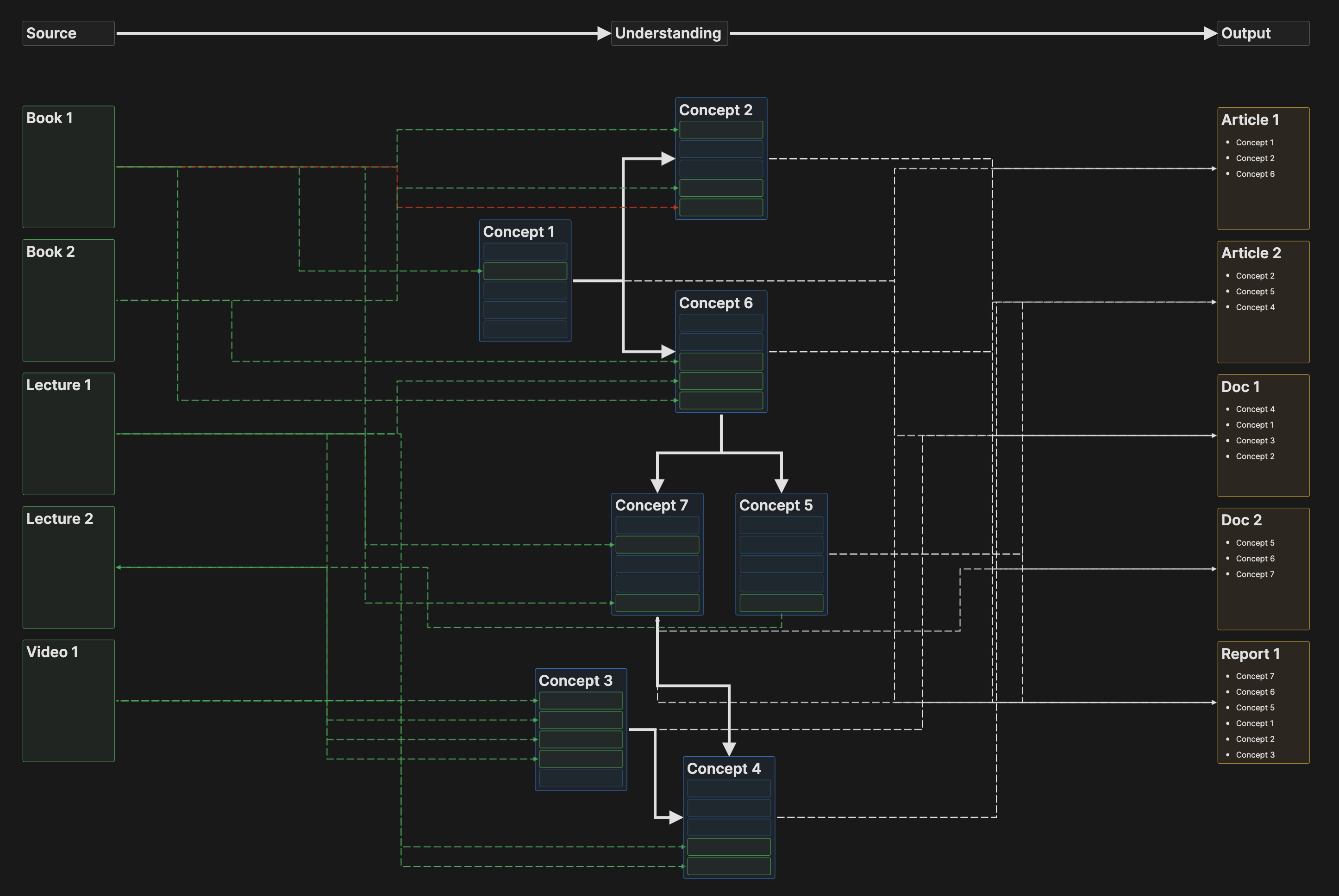

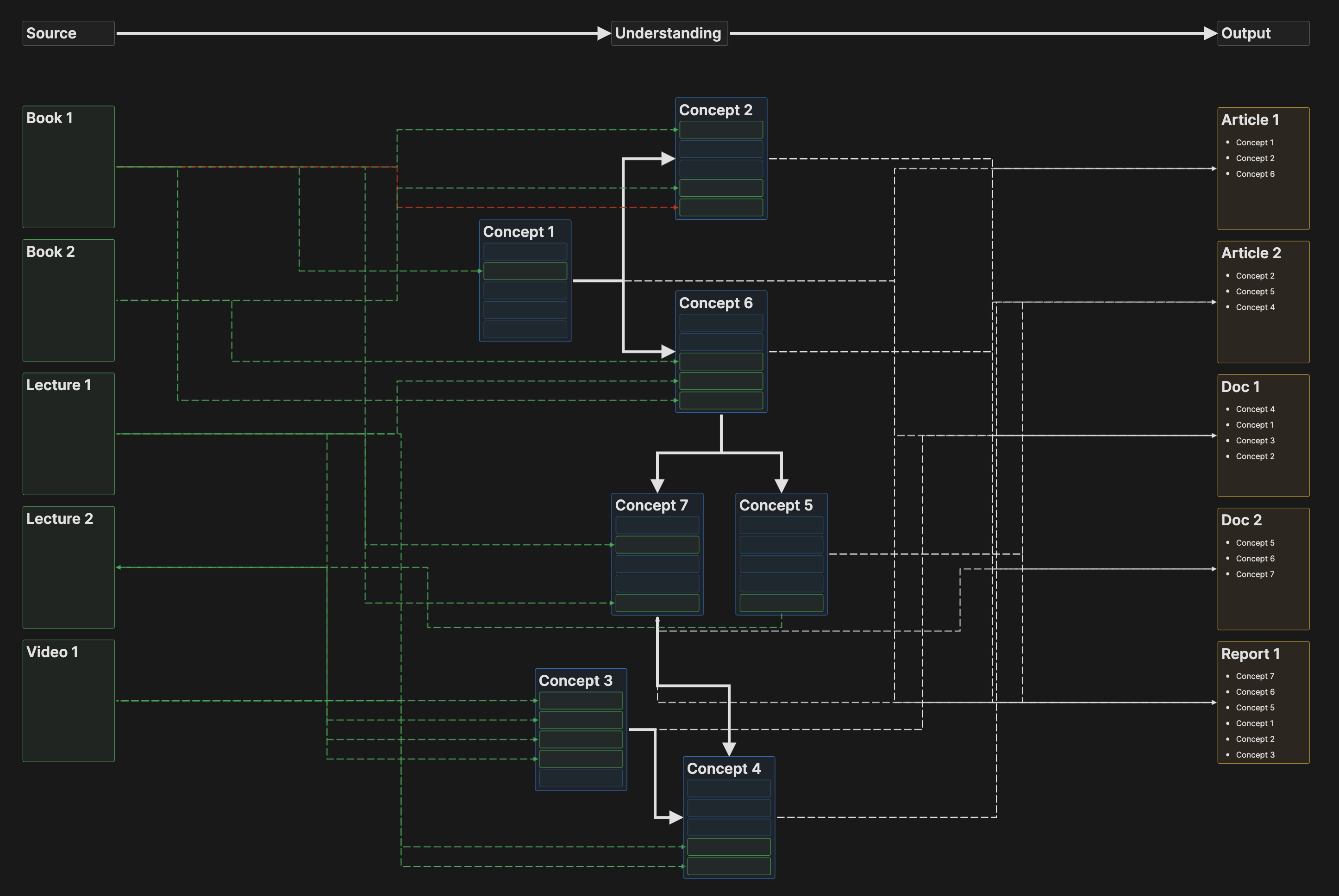

Under these core ideas, the processes of learning, research, planning, and output can be fully presented in the following diagram:

In this figure, on the left is source, which are the "literature cards" you wrote down while reading or attending lectures.

During my learning and research process, I extract useful concepts from these literature cards to create atomized "concept cards." Each concept card describes the concept in one sentence in the title and cites content from one or multiple pieces of literature to support this sentence. Every citation deepens my understanding and reflection of this concept.

As I learn and research, the original content of the literature cards will gradually be replaced by links to many concept cards. As I extract these concept cards from the literature cards step by step, I need to connect and fit them into a structure that makes sense to me. I can only truly understand and internalize a topic when I find such a structure for it.

In the future, whether I'm writing academic papers, work plans, or online articles, my process will involve linearly reassembling these concept cards into an "output card," which is an article meant for others to read. As I absorb and break down more and more "sources" during research, my "understanding" in the middle will deepen continuously, and the "output" on the right will naturally be of higher quality.

Closing thoughts

Although the topic of this article is about my method for acquiring, retaining, and applying knowledge, I do want to stress the importance of choosing the right tool to do so, because the design of a tool can radically change the way we subconsciously approach learning and form good and bad habits for it.

Seymour Papert, one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence and the constructionist movement in education, discusses his thoughts on this in Mindstorms:

For me, writing means making a rough draft and refining it over a considerable period of time. My image of myself as a writer includes the expectation of an “unacceptable” first draft that will develop with successive editing into presentable form. But I would not be able to afford this image if I were a third grader. The physical act of writing would be slow and laborious. I would have no secretary. For most children rewriting a text is so laborious that the first draft is the final copy, and the skill of rereading with a critical eye is never acquired. This changes dramatically when children have access to computers capable of manipulating text. The first draft is composed at the keyboard. Corrections are made easily. The current copy is always neat and tidy. I have seen a child move from total rejection of writing to an intense involvement (accompanied by rapid improvement of quality) within a few weeks of beginning to write with a computer. Even more dramatic changes are seen when the child has physical handicaps that make writing by hand more than usually difficult or even impossible.

Word processors can make a child’s experience of writing more like that of a real writer. But this can be undermined if the adults surrounding that child fail to appreciate what it is like to be a writer. For example, it is only too easy to imagine adults, including teachers, expressing the view that editing and re-editing a text is a waste of time (“Why don’t you get on to something new?” or “You aren’t making it any better, why don’t you fix your spelling?”).

As with writing, so with music-making, games of skill, complex graphics, whatever: The computer is not a culture unto itself, but it can serve to advance very different cultural and philosophical outlooks.

When building Heptabase, we aimed to design an environment that empowers you to externalize the process of identifying, dissecting, connecting, and grouping the concepts you have learned. That's why we built features such as the ability to dissect cards, move blocks across cards, build card relationships on a whiteboard, and reuse cards across multiple whiteboards. Together, these features form an environment that leverages the human capability of visual comprehension and visual memory with the computer's capability of data persistence and retrieval. With continued use of the tool to create understanding of your learning, you will start subconsciously adopting the habit of using the learning method described in this article. This is what ultimately matters—not just helping you take notes, but helping you become better at learning.

本文重點

將筆記視覺化的目的,是對你所學的知識建立深度理解。如果你的每一個筆記都非常長、如果你沒有把知識打碎、原子化,你能透過視覺化獲得的理解就會非常有限。真正的深度理解並不存在於「二本書之間的關聯性」裡頭,而是存在於「二本書中的所有概念之間的關聯性」裡頭。

只有當你將筆記原子化時,你才能透過筆記視覺化對你在乎的主題獲得深度理解。原子化指的並非你不能有很長的筆記,而是指每個概念筆記都只應包含一個概念,並以其內文來支撐這個概念。你必須能將每張概念卡片的核心概念用一句話總結,並以這句話當做是卡片標題以確保你一眼就能知道它在講什麼。

前言

身為一個時常閱讀的人,閱讀最讓我感到困擾的地方在於那些最好的書往往包含大量的內容,要完全地將這些內容消化、與我的既有知識整合有時並不容易。就算我將內容消化了,時間一久,當我在工作時突然想用以前所學的知識時,往往也很難單靠大腦記憶就回想起過去的所學。

這個問題不只發生在我身上,也發生在我認識的許多人身上。我想這也是大部分筆記軟體(又稱知識管理軟��體)想要解決的問題。但不幸的是,我覺得大部分的筆記軟體都過度專注在教你用什麼架構去保存筆記(例:階層、網狀、資料庫),卻沒有在**吸收知識(acquisition)、留存知識(retention)和應用知識(application)**等學習過程中最關鍵的環節提出改善方案。

在這篇文章中,我會分享我自身學習的實際案例,展示我設計的一個用 Heptabase 來有效獲取、留存和應用知識的方法。這個方法雖然不是學習的唯一方法,但是一個我驗證過極為有效的方法,而且我相信大部分的人都可以很快地學會將它應用在自己的學習中。

方法簡介

著名的費曼學習法認為深度學習一個主題最好的方式,就是嘗試把你在學習的主題教給小孩。我的想法是不管你想要教別人什麼,你都必須先釐清你要教的知識架構,並且有辦法把這樣的架構清楚地陳述出來。在我提出的方法中,我們可以透過五個簡單的步驟達到這件事情:

- 將閱讀的過程中看到的所有重要段落記錄下來

- 將紀錄下來的重要段落拆解成顆粒度更小的概念

- 畫出概念之間的關聯性

- 將相似的概念群組起來

- 將這些新學到的概念與過去所學的已知概念整合

下面這支影片是我實踐前四個步驟的過程。這支影片是一個真實案例的錄影,完全沒有經過事先的規劃。在這支影片中,我示範了我怎麼拆解 Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas 這本書的概念、獲得深度的理解。你不需要把影片看完(因為它長達四小時),但快速的看過�影片中的不同段落會讓你更清楚我從書本提取想法和建立理解的方式。如果你想玩玩看我在影片裡建立的白板,可以點擊這個連結。

[2024/01/03 更新] 我錄了一支教學影片示範並講解了我使用 Heptabase 執行這五個步驟的方式,大力推薦你看一下。

第一步:將閱讀的過程中看到的所有重要段落記錄下來

在我的方法論的第一步中,我們會需要把在閱讀過程中看到的重要段落記錄下來並且按照章節整理。這個過程的實作方式可能會根據你使用的工具而有所不同。如果你用的是電腦的閱讀器,你可以直接將文字從電子書複製貼上到一張 Heptabase 的卡片裡頭。如果你使用的是 Kindle 或 iPad 閱讀器,你可以把所有 Highlight 匯出成 Markdown 檔案再匯入到 Heptabase 裡頭。如果你讀的是實體書,你可以在每一個章節讀完時做一次筆記。

不管你採用哪種方式做筆記,你只要確保最終會產出一張書籍卡片,裡頭包含書中你在不同章節所紀錄的重要段落即可。

第二步:將這些紀錄下來的重要段落拆解成顆粒度更小的概念

當你將讀書筆記整理到一張書籍卡片以後,你可以創建一個白板,並透過 Heptabase 右上角的 Import Panel 將書籍卡片從 Card Library 匯進這個白板裡頭。舉例來說,我在 Reading Notes 這個母白板下創建了 Mindstorm 這個子白板,並且將 Mindstorms 這本書的卡片筆記放到了這個子白板上。

當我卡片放好之後,我會把它開到右側欄讓我更方便地瀏覽裡面的內容。我通常會先快速掃過一遍這張卡片的所有內容,然後將裡面所有重要的概念識別出來。當我決定要把一個概念萃取出來時,我會把與這個概念有關的區塊選取起來一口氣拖曳到白板上變成一張新的「概念卡片」。

光是創建卡片還不夠,我還會將這張卡片的核心概念用一句話總結,並以這句話當做是卡片標題以確保我一眼就能知道它在講什麼。接下來,我會將這張概念卡片裡頭的內容重新組織,讓它的結構更符合我的直覺;我也會看一下原本的書籍卡片裡頭有沒有其他與這張概念卡片相關的區塊,如果有的話,我就會把它們也拖進這張概念卡片裡頭。

第三步:畫出這些概念之間的關聯性

當我從書籍卡片中萃取出愈來愈多概念卡片後,我就會開始在這些概念卡片之間畫箭頭,或是把內容相近的卡片放在一起。如果我發現有二張概念卡片的內容在討論相同的想法,我會將它們合併;如果我發現一張概念卡片裡頭包含的資訊量太大,我會把它拆解成多張更小的概念卡片來保持卡片的顆粒度。

第四步:將相似的概念群組

在將所有書籍卡片的內容都轉成概念卡片後,我會關掉右側欄,開始專心把這些概念卡片之間的關聯性和群組關係建立起來。當我發現有多張概念卡片都跟某個子題有關時,我會將它們用 Section 包起來,並給這個 Section 一個名字。我在為 Section 取名時會跟為概念卡片下標題時一樣謹慎,因為這些名稱將會是未來回顧這個白板時第一眼看到的東西。

完整走完第二步到第四步通常會花上一小時到一天的時間,這個時間取決於這本書的長度和深度。當你產出最終的白板後,吸收知識的階段就結束了。在這個過程中,真正有價值的並不是你最終產出的這個白板,而是你在執行第二步到第四步的過程中建立知識架構、給每張概念卡片和 Section 下標題所投入的思考過程。深度的理解和洞察往往源自於將知識分解、重組、用自己的話語描述的這個過程。只有在走過這個過程後,這些知識才會真正變成你的知識。

在完成最終的白板排版(包含所有的箭頭和 Section)後,我會把原本的書籍卡片開到白板的右側欄,並將所有概念卡片和 Section 的連結重新貼回這張書籍卡片上。從下圖可以發現,這張書籍卡片中的每個連結顯示的內容都是某張概念卡片的標�題。這也是為什麼在第二步的時候,我會將每張概念卡片用一句話總結,並用這句話當作它的標題。唯有這麼做,我才可以在看書籍卡片時,不用把這些概念卡片的連結點開就知道它的重點是什麼。

舉例來說,如果我把一張概念卡片的標題命名為「工程師的次文化」(Engineers’ subculture),過了幾個月後回頭看,我很難想起這張卡片具體在講什麼。但如果我把這張概念卡片的標題命名為「覺得 BASIC 語言很簡單的工程師形成了一種次文化,這種次文化影響著教育界,導致教師們偏愛那些喜歡這種次文化的學生。」(Engineers who find BASIC easy to learn formed a subculture that is influencing the world of education to favor students who are most like that subculture.),那我未來回頭看時,就算不看內文也能回想起它的核心概念。

第五步:將這些新學到的概念與過去所學的已知概念整合

截至目前為止,我已經透過在白板上拆解並重組 Mindstorms 這本書的核心概念,對這本書的知識獲得了深度理解。但是光是理解這本書還不夠,我還想要真正做到將我在過去、現在和未來所學的知識全部整合起來。換句話說,我想要將這本書的概念卡�片與我以前為其他書和課程所寫的概念卡片整合在一起。

在做這件事情之前,我想先分享一個重要的學習觀念:只有當你將筆記原子化時,你才能透過筆記視覺化對你在乎的主題獲得深度理解。

很多人在第一次使用 Heptabase 這種視覺化筆記軟體時,會沿用舊的思維為每一本書或每一堂課寫一個筆記,這些筆記的內容都非常長、包含非常多要點。當你的筆記是這種型態時,你就很難從視覺化中獲得價值。

舉例來說,下面這張圖中有二張書籍卡片,每一張都有非常多內容。這二本書的內容確實是有關聯的,但是當我把它們的書籍卡片放在白板上相連時,這樣的視覺化並沒有帶給我新的價值,因為這麼做的效果跟把它們放在同一個資料夾中是一模一樣的。

將筆記視覺化的目的,是對你所學的知識建立深度理解。**如果你的每一個筆記都非常長、如果你沒有把知識打碎、原子化,你能透過視覺化獲得的理解就會非常有限,因為真正的深度理解並不存在於「二本書之間的關聯性」裡頭,而是存在於「二本書中的所有概念之間的關聯性」裡頭。**你要關聯的不是書籍卡片,而是你透過前面的四個步驟從這些書中拆解出來的、一張又一張獨立的概念卡片。

舉例來說,我最近在研究如何設計一種以計算機驅動的動態媒介,而 Mindstorms 和 The Early History of Smalltalk 這二本書的內容都與這個研究主題有高度相關。為了更好地做這個研究,我創建了一個叫「動態媒介」的白板,並將這二本書中與「動態媒介」有��關的概念卡片復用進來,使用心智圖的功能去組織它們,建立一個我自己獨一無二的理解架構。

正是因為我過去在閱讀這二本書時,有將裡頭最重要的知識和想法原子化、寫成一張張可以被我在未來復用的概念卡片,我現在才能在做研究輕易地將我過去的所學應用於新的題目上。我過去的所學不再只是靜靜地躺在資料夾中,而是可以成為我新的研究的基石。

註:原子化指的並非你不能有很長的筆記,而是指每個概念筆記都只應包含一個概念,並以其內文來支撐這個概念。如果內文很長,但全都能被用來支撐標題的概念,那麽這則筆記仍然是一個原子化的概念筆記。

如何學習和做研究

前面講了學習方法論在 Heptabase 的實踐,現在我想來總結一下這套方法論底層的核心思想:

- 我認為學習和研究的本質是將不同書籍、文獻、課程、經驗中學到的重要知識和想法拆解出來,用自己的方式去關聯、理解、內化,進而對人類已知和未知的事物建立深度理解。

- 我認為工作時寫的計畫和研究時寫的論文都是在將這些深度理解轉化成可以被執行和傳播的形式。

在這樣的核心思想下,學習、研究、計畫、產出的過程其實可以用下面這張示意圖來完整地呈現:

在這張圖中,最左邊是「素材」,也就是那些你在上課或閱讀的當下所寫下的「文獻卡片」。

我在學習和研究的過程中,會從這些文獻卡片中萃取出對我有用的重要概念,進而打造原子化的「概念卡片」。每個概念卡片都會在標題用一句話來描述這個概念,而內文會引用一到多份文獻的內容來支撐這句話,每一次的引用都會加深我對這個概念的理解和反思。

在學習和研究的過程中,文獻卡片的原始內容會逐漸地被替換成一堆概念卡片的連結。而當我一步步地將這些概念卡片從文獻卡片中萃取出來後,我需要找到一個合適的心智結構來安放它們。只有當我找到這個結構時,我才算是真正理解、內化了這這個主題。

在未來,不管我是在寫學術論文、工作計畫或網路文章時,我在做的其實都是在將這些概念卡片用線性的方式重組成專門給外人閱讀的、文章形式的「產出卡片」。隨著我在做研究時吸收並拆解愈多「素材」,我在中間的「理解」便能持續深化,右邊的「產出」自然也會有愈來愈高的品質。

結語

雖然這篇文章的主題在談吸收、留存和應用知識的方法論,但我最後想強調一下工具選擇的重要性,因為工具的設計往往會在潛意識下改變我們對學習的看法,並養成一些學習的好習慣和壞習慣。

Seymour Papert 是人工智慧和教育建構主義運動的先驅之一,他在 Mindstorms 這本書中探討了工具如何影響思考的想法:

對我而言,寫��作意味著草擬一個初稿,並在相當長的時間內對其進行修改和完善。我對自己作為一名作家的形象包含了一個「不被接受」的初稿,這個初稿會隨著持續的編輯而被打磨成最終呈現的形式。但如果我是一名三年級學生,我無法想像這樣的作法,因為寫作的物理行為相當緩慢和費力,而且我沒有秘書能幫我寫字。對於大多數孩子來說,重寫一篇文章是如此費力,以至於第一稿就成了最終的版本,這使得他們沒辦法培養用批判性地眼光重新檢視自己寫的初稿的能力。但是當孩子們有了文字編輯器後,這種情況會有戲劇性的改變。初稿變成是在鍵盤上創作的。糾正錯誤變得容易。當前的版本總是乾淨整潔的。我見過一個孩子在開始使用電腦寫作幾週後,從完全拒絕寫作到積極參與(並伴隨著品質的快速提升)。當孩子們因生理缺陷而手寫困難或甚至不可能時,這種情況變得更加戲劇性。

文字編輯器可以讓孩子的寫作體驗更像真正的作家。但如果身邊的成年人無法欣賞作家的感受,這一點就會受到削弱。例如,人們很容易想象成年人(包括老師)會表達這樣的觀點:修改和重新編輯文本是浪費時間的(「為什麼不做些新的事情呢?」或「你沒有讓它變得更好,為什麼不修正你的拼寫?」)。

寫作、音樂創作、技巧遊戲、複雜圖形等等,都可以用同樣的方式來看待:電腦不是一個獨立的文化,但它可以用於推進非常不同的文化和哲學觀點。

在打造 Heptabase 時,我們的目標是設計讓你可以將大腦學習知識的過程外部化的環境,讓你可以用眼睛和手去對概念進行識別、拆解、連接和分組。這就是為什麼我們開發拆解卡片、在卡片之間移動區塊、在�白板上建立卡片關係、在多個白板之間重複使用卡片等功能。這些功能共同構成了一個環境,讓你能更好地運用人類的視覺理解和視覺記憶能力以及電腦的資料持久性和檢索能力來學習。當你愈常使用這個工具來對你的所學建立架構,你就會下意識地將這篇文章中描述的學習方法變成自己的習慣,而這才是最重要的 — 工具不只能讓你記筆記,更讓你成為一個擅長學習的人。

本文の要点

ノートを視覚化する目的は、学んだことを深く理解することです。すべてのノートが非常に長く、知識をより小さな部分に分解しない場合、視覚化から得られる理解は非常に限定的になります。本当の深い理解は、「二冊の本の間の関係性」ではなく、「これら二冊の本のすべての概念の間の関係性」から来るのです。

ノートをアトム化することで、自分が気になるトピックについて深い理解を得ることができます。アトミック・ノートテイキングとは、長いノートを持つことができないということではなく、各概念カードが一つの概念のみを含み、その内容で裏付けられているということを意味します。明確性を確保するために、常に一つの概念を一文で説明し、その文を概念カードのタイトルとするべきです。

序文

私はたくさん読みます。私にとって、読書における最も困惑する問題は、素晴らしい本には多くの内容が含まれており、それを完全に消化し、既存の知識と統合することが容易でないということです。内容を完全に消化したとしても、私は過去に学んだ知識を純粋に記憶から呼び出すことがしばしば難しく、それが私が学んだことを現在の仕事に適用するのが難しくなる要因となります。

多くの人々がこの学習の問題に直面していることを私は知り、この問題は多くのノートテイキング(または知識管理)ツールが解決しようとしているものです。残念なことに、これらのツールのほとんどはノートの保存方法(フォルダ、グラフ、関係データベースなど)に重点を置きすぎており、習得(知識の理解)、保存(過去の知識の思い出し)、応用(現実のシナリオでの知識の適用)という学習の重要な側面を無視しています。

この記事では、私と私のチームが学習と研究のために作成したツールであるHeptabaseを使用して、知識の習得、保存、応用の効果的な方法を開発した実世界の例を共有します。これは学習の唯一のワークフローではありませんが、私にとって非常に効果的であり、ほぼ誰でも自分の学習に応用できると信じています。

方法の概要

有名なフェインマン学習テクニックは、あるトピックの深い理解を開発するための最も良い方法は、それを子供に教えることだと示唆しています。私は言いたいのは、何かを教えるときは、まず知識の構造を把握し、その構造を明確に表現できるようにする必要があるということです。私が開発したメソッドは、以下の5つのステップでそれを実現するのに役立ちます:

- 読書中に重要な段落をハイライトします。

- 本の内容を細かい概念に分解します。

- これらの概念の関係をマッピングします。

- 類似した概念をグループ化します。

- これらの新しく学んだ概念を既知の概念と統合します。

以下は、このプロセスをどのように行うかを示す動画です。この動画はステージ設定されたものではありません。私が読んだ本である Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideasの理解を開発する方法の実際の例です。完全に見る必要はありません(4時間の長さです!)、しかし、動画の異なる部分をスキャンすることで、本から中核的な概念を抽出し、理解を深める方法が明確にわかるでしょう。動画で作成したホワイトボードを探索したり、遊んだりしたい場合は、こちらのリンクをご覧ください。

[2024/01/03 更新] Heptabase を使用して、以下の5つの手順を実行する方法をデモンストレーションおよび解説したチュートリアル動画を録画しました。ぜひご覧ください。

ステップ1:読む際に重要な段落をハイライトする

プロセスの最初のステップは、読んだ本から重要な段落をハイライトし、章ごとに整理することです。

使用するリーダーによって、ハイライトのプロセスは異なる場合があります。デスクトップリーダーを使用している場合は、テキストをコピーしてHeptabaseのカードに貼り付けるだけです。KindleやiPadリーダーを使用している場合は、書籍のすべてのハイライトをMarkdownファイルとしてエクスポートし、それをHeptabaseにカードとしてインポートすることができます。物理的な本を読んでいる場合は、各章を読み終えるたびにHeptabaseにメモを取ることができます。

ハイライトを作成するために使用するツールは重要ではありません。重要なのは、ハイライトを含む一つの大きなカードを作成することです。それには、さまざまな章のハイライトが含まれています。

ステップ2: 本の内容を詳細な概念に分解する

本のカードが完成したら、ホワイトボードを作成し、カードライブラリのインポートパネルを介してそのカードを追加することができます。私の例では、Reading Notesという親ホワイトボードの下にMindstormというサブホワイトボードを作成し、Mindstormsの本のカードをこのサブホワイトボードにドラッグしました。

カードが準備できたら、右の分割パネルでそれを開いて、内容をよりよく見ることができます。通常、重要な概念を特定するために、すべての内容をざっと見渡します。抽出したい概念があると判断したら、関連するブロックを選択し、それらをホワイトボードにドラッグして新しいカードを作成します。

単に概念カードを作成するだけでは不十分です。明確性を確保するために、私は常にその概念を1文で説明し、その文を概念カードのタイトルとして使用します。 そして、この概念カードのカードの内容を自分にとって理解しやすい構造に再編し、場合によってはオリジナルのブックカードから他の関連ブロックをこの概念カードに引っ張り込むことさえあります。

ステップ3: これらの概念間の関係をマッピングする

**オリジナルの本のカードからさらに概念カードを抽出すると、それらの間に接続を追加したり、似たような概念カードを隣り合わせに配置したりします。**同じアイデアに関する2つの概念カードを見つけた場合は、それらを1つに統合します。他の場合では、1つの大きな概念カードを細分化して複数の小さなカードに分割することもあります。これにより、詳細さが確保されます。

ステップ4: 似たような概念をグループ化する。

オリジナルのブックカードからすべての内容を概念カードに抽出した後、分割パネルを閉じて、マッピングとグループ化の関係性に取り組みます。よくあるケースとしては、同一のサブトピックに関連する複数の概念カードが見つかることです。このような場合、それらの概念カードをセクションにグループ化し、そのセクションに名前を付けます。セクションの命名は、概念カードの命名と同様に注意深く行うべきです。なぜなら、これらの名前は将来このホワイトボードを再訪した際に最初に思い出すポイントになるからです。

ステップ2から4を完了するには通常、1時間から1日全体かかります。本の長さや深さによります。最終的なホワイトボードを作成したら、知識取得フェーズは終了です。このプロセスで本当に価値があるのは、最終的なホワイトボードを作成することではなく、ステップ2から4までの間で知識構造を確立し、各概念カードとセクションにタイトルを付ける際に投じる思考プロ�セスです。深い理解と洞察は、知識を分解し、再構築し、自分の言葉で説明するプロセスから生まれます。このプロセスを経ることで、知識は本当にあなた自身のものとなります。

最終的なホワイトボードのレイアウト(すべての矢印とセクションを含む)を完成させた後、私はこのホワイトボードの右側の分割パネルで元の本のカードを開き、すべての概念カードとセクションへのリンクを再度この本のカードに貼り付けます。下の図では、この本のカード内の各リンクが概念カードのタイトルを表示していることがわかります。これが、2つ目のステップで各概念カードを一文でまとめ、その一文をそのカードのタイトルとして使用する理由です。そうすることでのみ、これらの概念カードのリンクを開かずに本のカードを読むときに、この本のコアコンセプトを確認することができます。

例えば、「エンジニアのサブカルチャー」といったコンセプトカードのタイトルをつけた場合、数ヶ月後にそれを振り返った時、そのカードが具体的に何についてのものかを思い出すのは難しいでしょう。しかし、「BASICの学習が容易なエンジニア達は、そのサブカルチャーに最も似ている学生を優遇する教育の世界に影響を与えるサブカルチャーを形成した」というタイトルをこのコンセプトカードにつけると、内容を読まずともそのタイトルだけで将来的にも中心的な概念を思い出すことができます。

ステップ5: これらの新たに学んだ概念を以前に知っていた概念と統合する

これまでに、マインドストームという本のコアとなる概念をホワイトボード上で分解し、結びつけることで深く理解を深めてきました。しかし、この本を理解するだけでは足りません。過去、現在、未来において学んだ全ての知識を真に統合したいと思っています。つまり、この本の概念カードを過去に他の本や講義のために書いた概念カードと統合したいと思っています。

これを始める前に、大切な学習マインドセットを共有したいと思います: 視覚的なノート取りを通じて、あなたが気にするトピックについて深い理解を得ることができるのは、あなたのノートを原子化したときだけです。

Heptabaseのような視覚的なノート取りアプリを初めて使用する多くの人々は、古いノート取りの方法を引き続き使用し、1つの本や講義ごとに1つのノートを書き、多くの概念を含む非常に長いノートを作成します。あなたのノートがこの形式である場合、視覚化から価値を得るのは困難です。

たとえば、下の図には、それぞれ大量の内容を持つ2つの書籍カードがあります。これら二つの本の内容は関連していますが、ホワイトボード上でこれら二つの本のカードをつなげることは、それらを同じフォルダに入れるのとほぼ同じであるため、新たな価値を提供しません。

あなたが学んだことを深く理解するためにノートを視覚化するのが目的です。**あなたのすべてのノートが非常に長く、知識をより小さな部分に分解しないならば、視覚化から得られる理解は非常に限定的になります。真の深い理解は、「2冊の本の間の関係」からではなく、「これら2冊の本に含まれるすべての概念の間の関係」から来ます。**繋げるべきなのは本のカードではなく、前の4ステップを使ってこれらの本から抽出した個々の概念カードです。

例えば、私は最近、どのようにコンピュータ駆動のダイナミックメディアを設計するかについての研究をしており、両書籍マインドストームとスモールトークの初期の歴史は、この研究トピックに大いに関連があります。この研究をより効果的に行うために、私はダイナミックメディアというホワイトボードを作成し、これら二つの本からダイナミックメディアに関連する概念カードを再利用し、それらをマインドマップを使って組織化し、独自の理解フレームワークを確立しました。

それは私がこれら二つの本を以前読んだ際に、最も重要な知識やアイデアを抽出し、再利用可能な概念カードに分解したからです。そのため、今では以前の学習を新しい研究トピックに容易に適用することができま��す。私の過去の知識はもはや無駄にフォルダに眠っているのではなく、最新の研究作業の土台となっているのです!

注: アトミック・ノートテイキングは長いノートを持つことを意味していません。それは各概念カードが一つの概念のみを含み、その内容によって支えられているべきであるということを意味します。もしも内容が長くても、それが全体としてタイトルの概念を支持しているなら、そのカードはまだアトミックな概念カードと言えるでしょう。

学びと研究の方法

Heptabaseで学習方法論を実装する方法を共有した後、この方法論の背後にあるコアなアイデアをまとめておきたいと思います:

-

私は、学びと研究の本質は、書籍、文献、講演、そして経験から重要な概念を分解し、抽出することであると信じています。そして、これらの概念を自分自身の方法でつなげ、理解し、内化することで、人間が知らないことと知っていることについての深い理解を築くべきです。

-

すべての仕事の計画や研究論文は、この深い理解を実行可能で伝達可能な形に変換することで生まれる製品だと考えています。

これらの中心となる考え方の下では、学習、研究、計画、アウトプットのプロ��セスは以下の図によって完全に表現することができます:

この図では、左側がソースで、これはあなたが読書したり講義を聞いたりしている間に書き留めた「文献カード」です。

私の学習と研究の過程では、これらの文献カードから有用な概念を抽出し、「概念カード」と呼ばれる微細化されたカードを作成します。各概念カードは、タイトルで一文で概念を説明し、この一文を支持するために、一つまたはそれ以上の文献からの引用を掲述します。それぞれの引用は、この概念に対する私の理解と反省を深めます。

学習や研究を進めていくと、文献カードの元の内容は徐々に多くの概念カードへのリンクに置き換えられます。これらの概念カードを文献カードから一歩一歩抽出し、私にとって意味のある構造に結びつけて整合させる必要があります。そのような構造を見つけたときにだけ、私は話題を真に理解し、内面化することができます。

将来、私が学術論文や仕事の計画、またはオンラインの記事を書いている時、私のプロセスはこれらの概念カードを「アウトプットカード」、つまり他の人が読むための記事に一本筋を通して再構成することになります。研究中にますます多くの「ソース」を吸収し分解していくと、中央の「理解」は次第に深まり続け、右側の「アウトプット」は自然と質が高くなるでしょう。

結びの言葉

本記事のトピックは、知識の獲得、保持、応用の方法についてですが、適切なツールを選ぶことの重要性も強調したいと思います。なぜなら、ツールの設計によって、学習への潜在的なアプローチ方法や、それに対する良い習慣や悪い習慣が根本的に変わってしまうからです。

人工知能や建設主義教育運動の先駆者の一人であるセイモア・パパートは、彼の著書である「マインドストーム」で、このことについての考えを述べています。

私にとって、執筆とは、まずはざっくりとした下書きを作り、それを時間をかけて磨き上げることを意味します。私は、最初の下書きは「受け入れがたい」と思われるものであり、連続した編集を経て、見栄えの良い形になるという期待を抱いています。しかし、私が3年生だったらこのイメージを持つことはできませんでした。手書きは時間がかかり、苦労が伴います。私には秘書もいませんでした。ほとんどすべての子どもにとって、テキストの再編集は非常に困難であり、初稿が最終作になり、批評的な目で再読するスキルは身につきません。しかし、テキストを操作できるコンピュータにアクセスできるようになると、これは劇的に変化します。最初の下書きはキーボードで作成されます。修正も簡単に行えます。現在のコピーはいつもきれいで整然としています。私は、コンピュータでの執筆を始めて数週間後に、執筆に対する徹底的な関与(品質の急速な向上とともに)へと進展する児童を見たことがあります。手書きが通常よりも困難または不可能な身体的な障��害を持つ子どもには、より劇的な変化が見られます。

ワードプロセッサは、子どもたちの執筆体験を実際の作家のようにすることができます。しかし、その子どもを取り巻く大人たちが作家としての体験を理解することができなければ、その効果は損なわれることがあります。例えば、大人たち、教師を含めて、テキストの編集や改編が時間の無駄だと言ったり(「新しい課題に取り組みなさい」とか、「スペルを直す方が良いでしょうに、どうしてそれに時間をかけるの?」など)きっぱりと述べることも簡単です。

執筆の場合と同様に、音楽制作や技術的なゲーム、複雑なグラフィックなども同じです。コンピュータはそれ自体が独自の文化ではなく、非常に異なる文化的、哲学的な見方を進めるツールとなり得るのです。

Heptabaseを構築する際には、学んだ概念の特定や分析、結び付け、グループ化のプロセスを具現化する環境を設計することを目指しました。そのために、カードの分解やブロックの移動、ホワイトボード上でカードの関係を構築し、複数のホワイトボードでカードを再利用するなどの機能を開発しました。これらの機能は、人間の視覚理解力と視覚記憶力を活用しながら、コンピュータのデータの持続性と検索能力を活かす環境を形成しています。このツールを使って学習の理解を深めることで、無意識のうちに本記事で説明されている学習方法を身につける習慣を自然に身につけるようになります。これが最も重要なことであり、メモの取得だけでなく、学び方を向上させることに役立ちます。

このセクションの翻訳は ChatGPT によって生成されました。もし、より正確または繊細な翻訳が可能だとお考えの場合、pj@heptabase.com までお気軽にご連絡ください。皆様のフィードバックを大変感謝しております!