- English

- 中文

This article was published on October 29, 2021 by Alan Chan, co-founder of Heptabase, one month after the company was incorporated.

Foreword

After finishing the first three articles (My Vision: The Context, My Vision: A New City, My Vision: A Forgotten History), I will begin introducing the next generation of the internet that I am building, Heptabase, from different perspectives starting with this article.

Heptabase’s vision is to create a contextualized knowledge internet, and an ecosystem of tools surrounding this knowledge internet, to augment the individual and collective intelligence of knowledge workers around the world. In this article, I will introduce this vision from the perspective of “The lifecycle of human knowledge work.”

The lifecycle of human knowledge work

Human knowledge work has a lifecycle: exploring → collecting → thinking → creating → sharing. For example, I might explore ideas and information online, collect valuable insights and data into a note-taking app, use a whiteboard tool to think and organize my thoughts, then create content through a writing tool once my ideas take shape, and finally share the results back to the internet for others to explore.

The drawback to the process is that I’m constantly switching tools. The context of an idea is scattered across different tools, making it hard to trace and integrate. Humans have bad memories. An idea loses most of its meaning if I can’t remember the context behind it.

Heptabase helps knowledge workers bridge the gaps between different parts of the knowledge lifecycle and preserve the thinking context behind all ideas. The knowledge internet we’re building focuses on optimizing three dimensions: information interoperability, context retrieval, and collective knowledge creation.

Information Interoperability

To build a contextualized knowledge internet, the first step is to ensure that information across all stages of the lifecycle can be interoperable. Currently, the software world approaches this problem in two major ways.

The first approach is to increase the capabilities of a single piece of software. This is often done by packing many features into one tool (e.g., Notion), or by adding plugin systems that extend the tool for different use cases (e.g., Obsidian). While this can cover more use scenarios, it typically leads to a steep learning curve, reduced usability, and fragmented focus—making no single feature truly excellent. Additionally, endless plugin extensions can quickly become hard to manage and maintain.

The second approach is to integrate multiple tools through APIs (which may come from different apps or be natively provided by the file system). This is the most common approach to combining software capabilities today. However, it comes with high development and maintenance costs and requires many compromises in data format compatibility and synchronization. If integration is achieved by copying data between tools, it’s almost impossible to truly achieve the experience of “using one tool inside another.” But if multiple tools try to share a single database without a universal protocol, the risk of data corruption grows exponentially as the number of tools increases.

Do we really have to compromise between these two directions? After careful thought, I believe that to build the contextualized knowledge internet we envision, the system must follow three core principles:

-

All software must share the same data format.

-

All software must follow a universal protocol for data processing.

-

Software should be as decoupled from data as possible, avoiding direct data ownership.

Heptabase is built on these three principles.

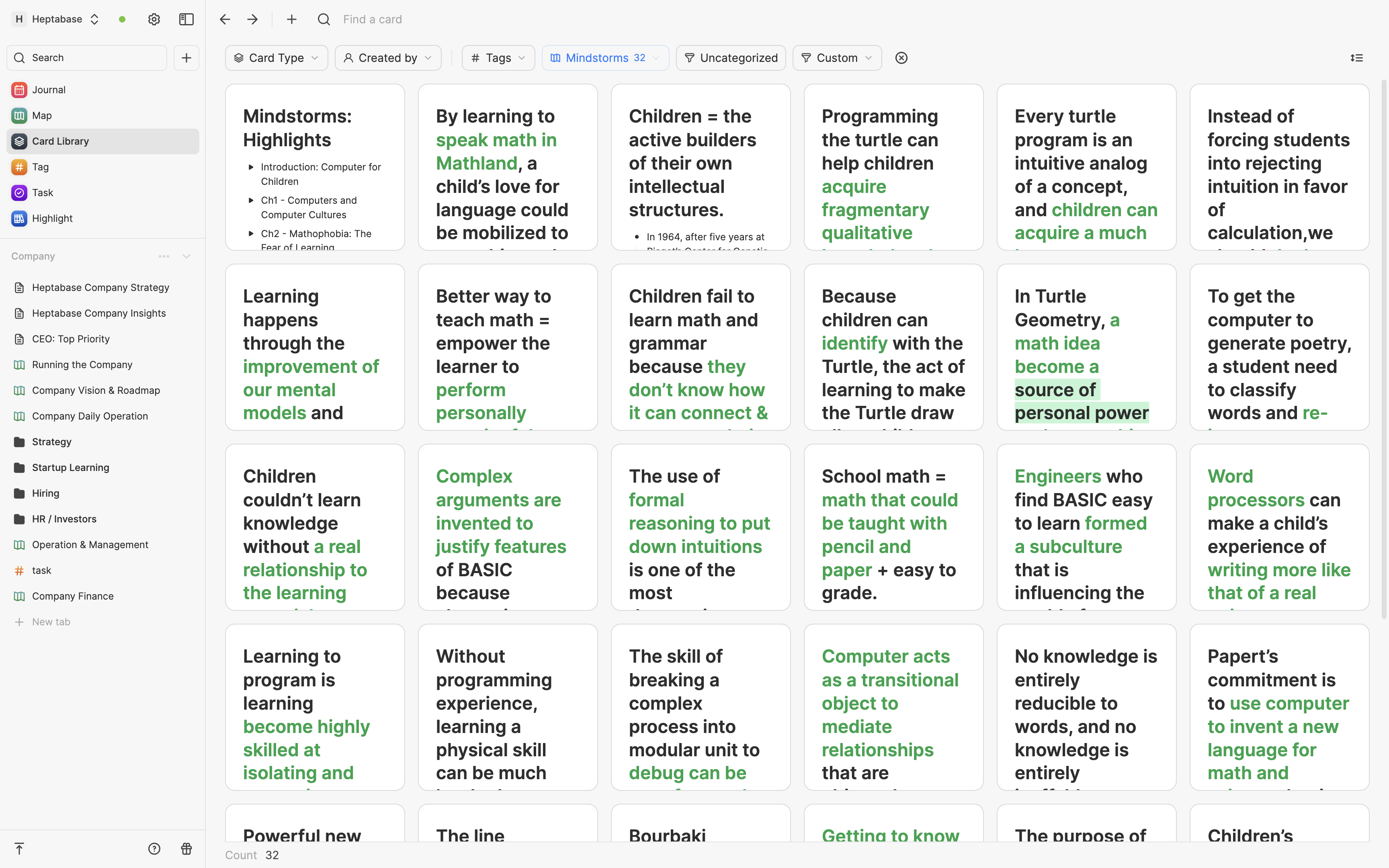

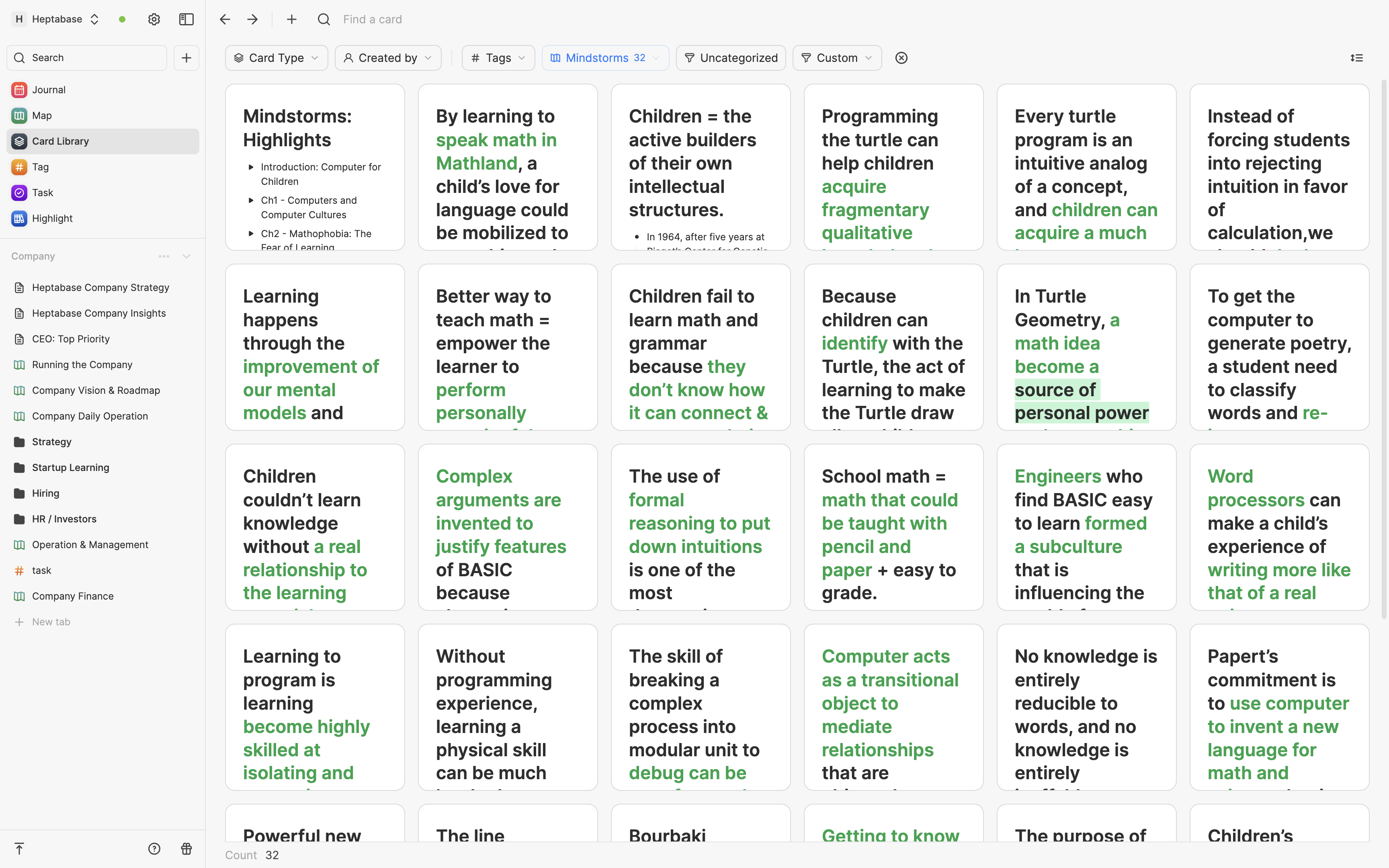

In the system I envision, all data are “cards.” Cards can be extended into many types: they can be notes, PDFs, videos, images, e-books, spreadsheets... these basic types, or compounds, gene sequences, drugs, algorithms... these special data objects in professional fields. All cards will use a universal data format to store their metadata, and all software on this system, which I call Meta Apps, will use a universal protocol to read and edit these metadata. In this way, each Meta App can maintain its own usability, while Heptabase, as the operating system that carries these Meta Apps and as the browser that opens Meta Apps and cards, can both ensure that data are universal among Meta Apps—eliminating the cost of connecting data between them—and decouple data and Meta Apps through the abstraction layer of metadata, allowing us to ensure that all Meta Apps share the same data format while greatly reducing the risk of data being corrupted by Meta App developers.

Context retrieval

To build a contextualized knowledge internet, the second step is to ensure that the thinking context behind all knowledge and ideas can be fully preserved and traced. When you see an idea, you should be able to find how it was created and in what context it was used.

For all human knowledge and ideas, there is always an input before there is an output. “Tracing the thinking context” helps us understand what kind of input leads to what kind of output. To achieve this goal, we must integrate the “collecting,” “thinking,” and “creating” stages of the knowledge lifecycle.

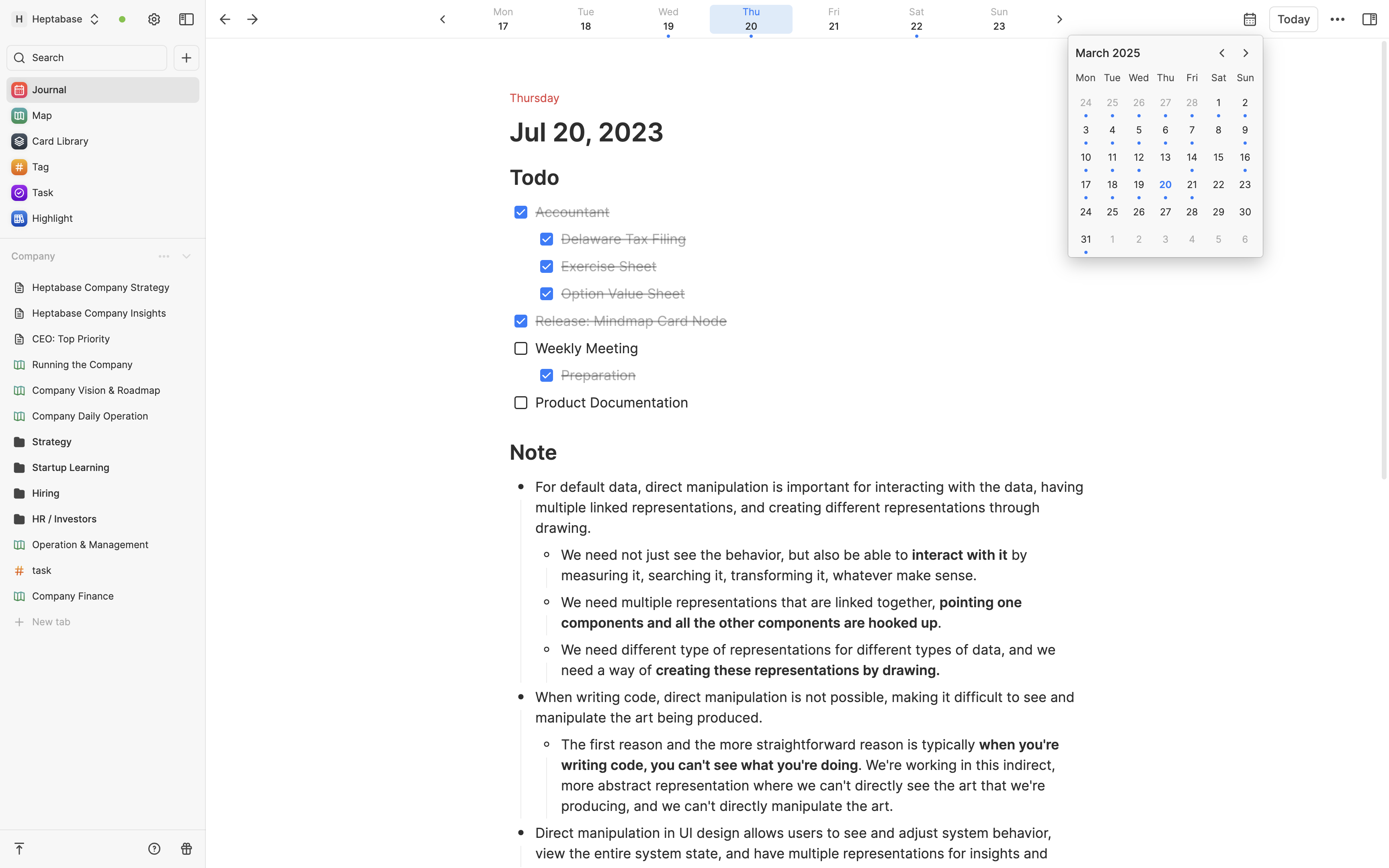

The principle of collecting is “fast.” Ideas are fleeting, and a good collecting tool should have very low friction and can capture ideas as they arise. In Heptabase, the Meta App responsible for this task is called Journal. You can pour ideas into it anytime without creating an actual note.

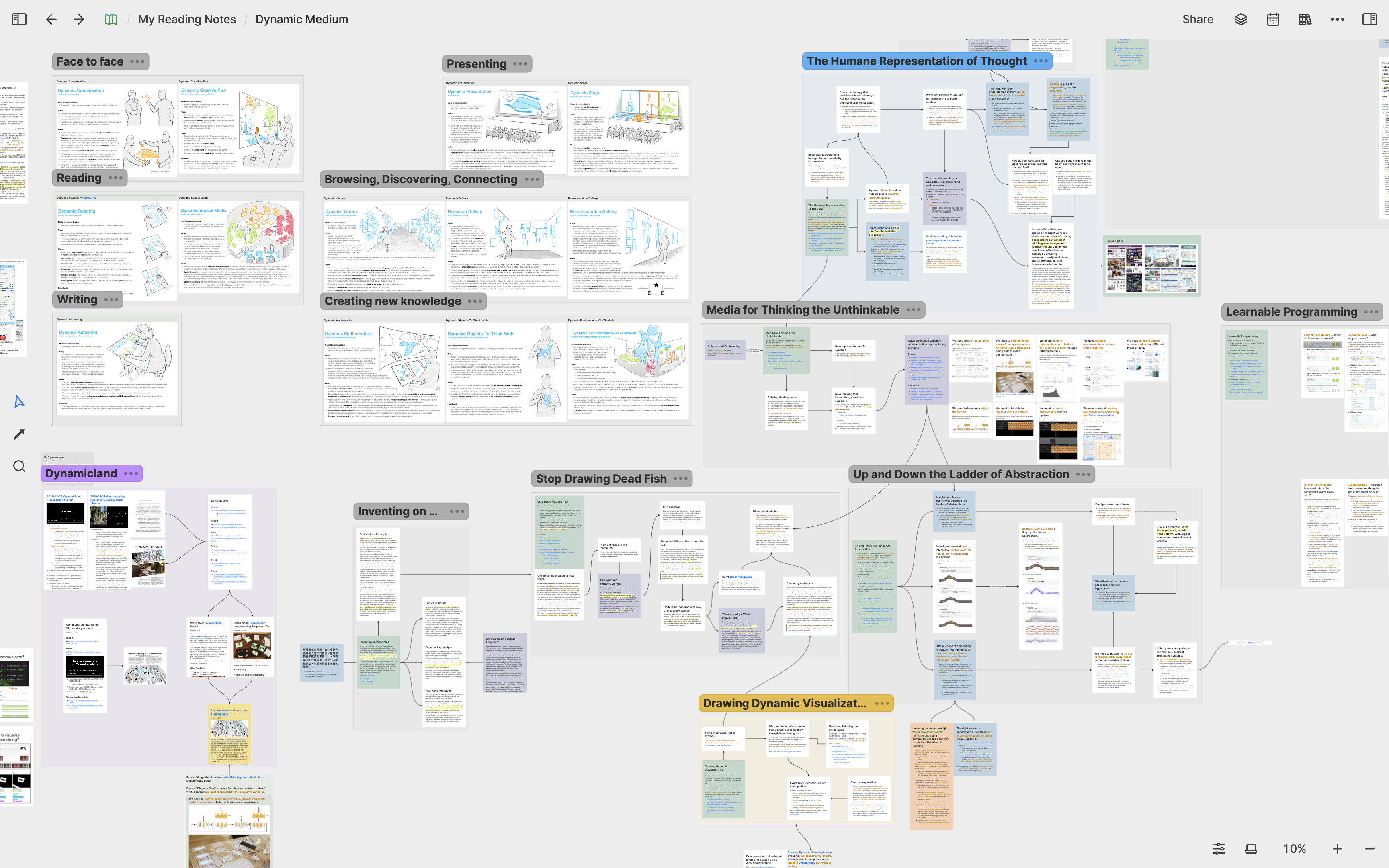

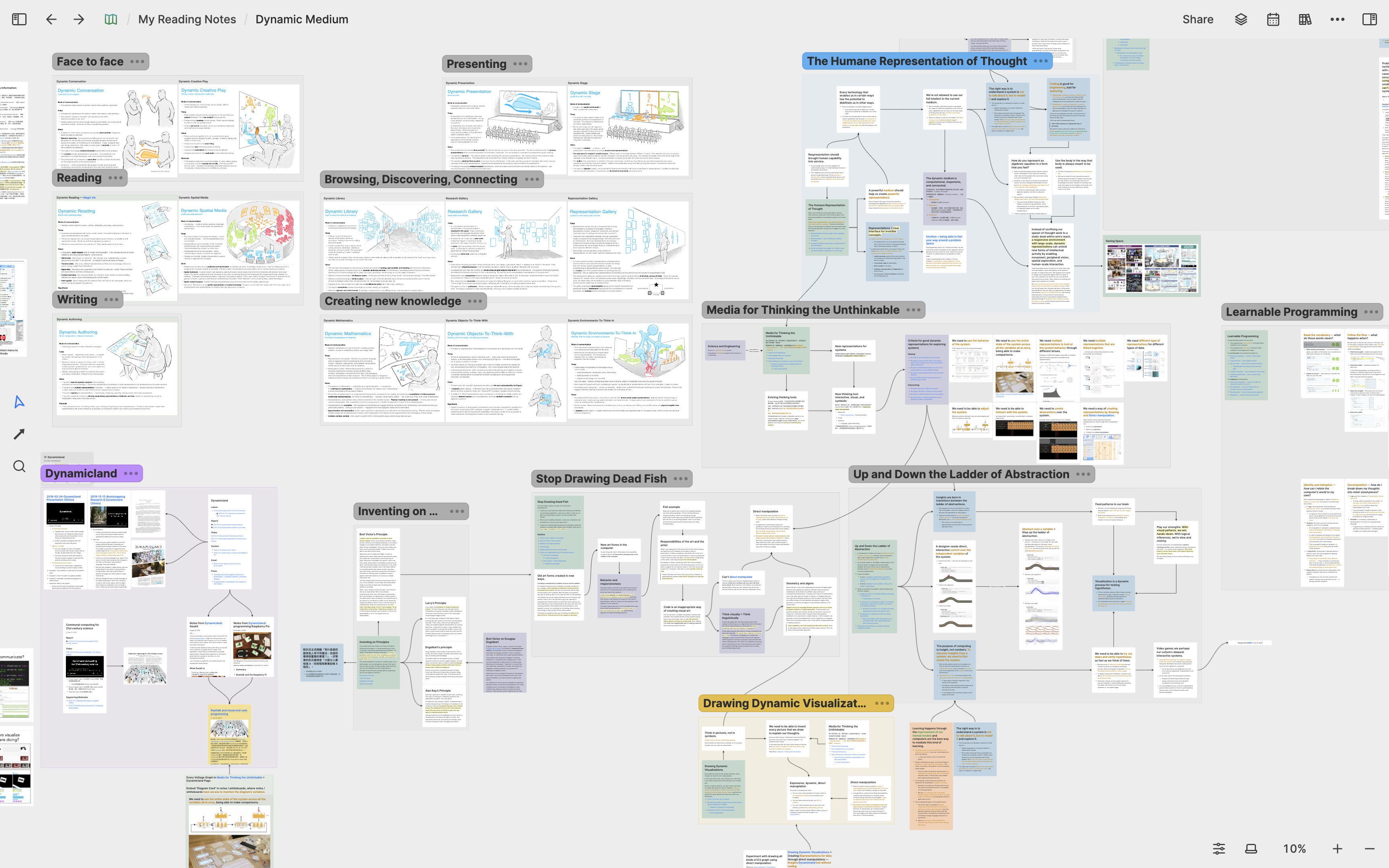

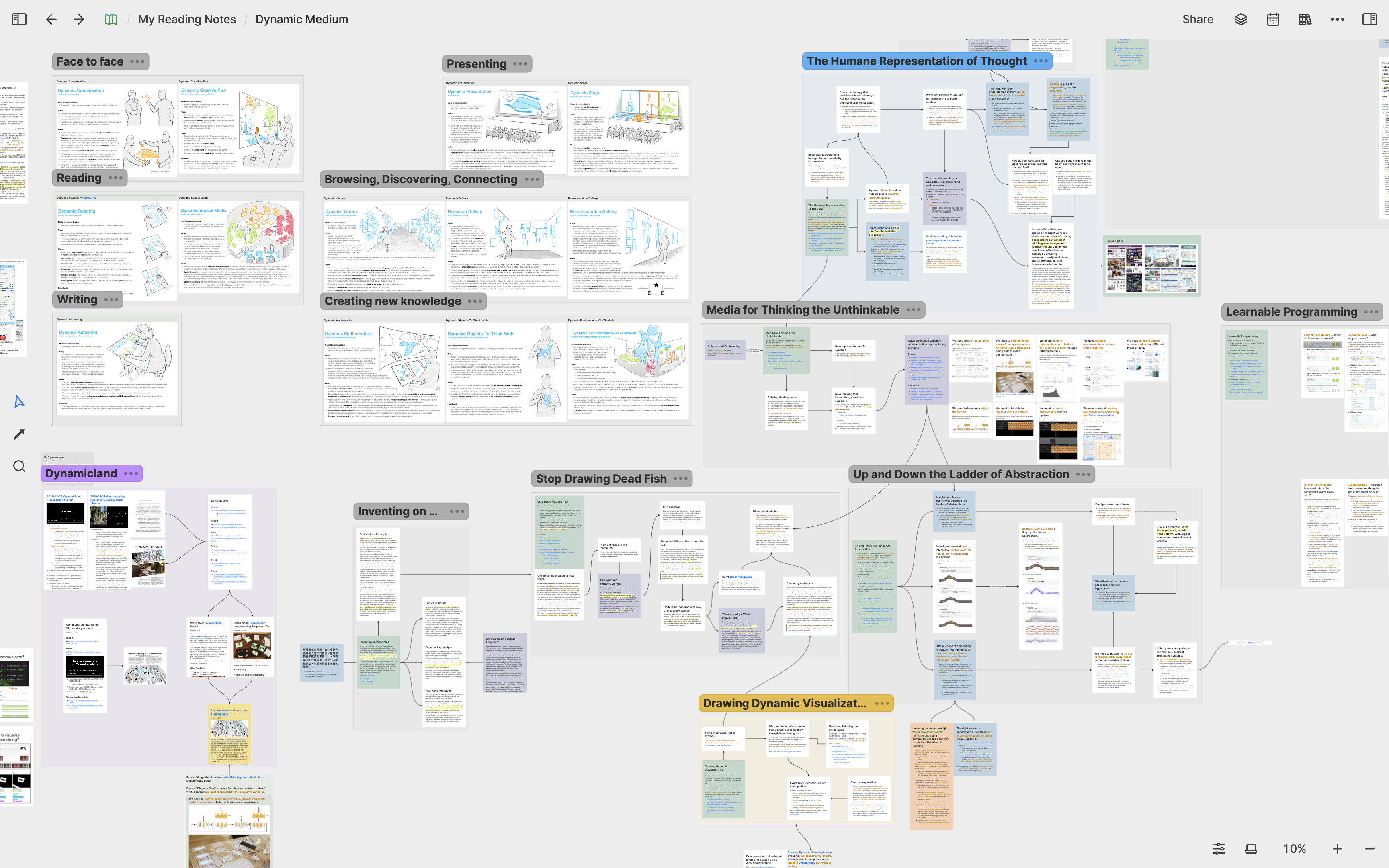

The principle of thinking and creating is "visual." To clarify our thinking, we often have to visualize the big picture of our ideas. Moving and reorganizing information on visual space is a critical process to augment thinking. In Heptabase, the Meta App responsible for this task is called Whiteboard. You can pull out contents from Journal onto an infinity whiteboard space to create cards and arrange these cards to clarify your thinking structure. A card can appear on multiple whiteboards at the same time.

Journal and Whiteboard, as Meta Apps, do not own the data of cards. They read and reference the card database of Heptabase, and the only data they have is metadata for presenting cards. For example, Whiteboard does not own the cards’ contents but store the cards’ spatial attributes (shape, color, arrow) on different whiteboards.

This sharing of card databases ensures that each Meta App is not overly complex but is well integrated into a workflow, avoiding untraceable gaps between different stages of the knowledge lifecycle. When you see a card, you can trace when it was created, what other cards have mentioned it, what whiteboards it appears on, and its position in different mental frameworks.

Collective knowledge creation

To build a contextualized knowledge internet, the final step is to let individual thinking interact and enable collective knowledge creation that can’t be done with any individual mind on their own. To achieve this goal, we must integrate the “sharing” and “exploring” stages of the knowledge lifecycle.

When it comes to collective intelligence, the examples that come to our mind are software like Notion and Miro, which put “shared workspace” and “real-time collaboration” in their value proposition. However, there are three main problems with such products that make collective intelligence difficult to emerge.

First, these shared workspaces force everyone in the team to use the same information architecture from the top-down, rather than letting everyone use the one that works for them.

Second, it’s easy to result in disorder when everyone’s thinking overlaps in the same workspace. It’s hard to know which documents are outdated and which are still in use. If many people have edited a document, it’s hard to trace why they edited it and the thinking context behind each editing.

Third, it’s easy to result in groupthink when entering real-time collaboration before the ideas from individuals get matured, which is terrible for independent thinking. For efficiency reasons, collaboration often takes a majority decision approach to develop ideas, resulting in an individual’s unique ideas being unexpressed and stifled early.

At Heptabase, we advocate bottom-up “asynchronous sharing” based on “personal workspace.” When knowledge workers want to collaborate, asynchronous sharing from a personal workspace allows them to track each other’s thinking clearer and reuse each other’s ideas and knowledge without disturbing anyone’s independent thinking process.

Instead of sharing an idea, we can share an entire thinking context that uses ideas as a unit. Every idea in each thinking context can be used by other thinking contexts. Heptabase’s context-tracing ability allows you to explore different thinking contexts behind any idea you see.

Summary

In short, from the perspective of “The lifecycle of human knowledge work,” we are building an ecosystem of tools to help knowledge workers integrate their knowledge lifecycle of exploring → collecting → thinking → creating → sharing. Our guiding principle is to optimize information interoperability, context retrieval, and collective knowledge creation, with the ultimate aim of evolving a contextualized knowledge internet.

In the next article, I will provide a detailed introduction to the structure of the Heptabase system, as well as the roadmap of our iterations for this system.

這篇文章是由 Heptabase 的共同創辦人詹雨安於 2021 年 10 月 29 日發布,當時 Heptabase 公司剛成立一個月。

前言

在完成 My Vision: The Context、My Vision: A New City、My Vision: A Forgotten History 這三篇文章後,從這篇文章開始,我將開始用不同的維度去介紹我正在打造的新一代網際網路:Heptabase。

Heptabase 的願景是打造出一個脈絡化的知識網路,以及圍繞在這個知識網路周圍的工具生態,進而強化全世界知識工作者的個體和集體智能。在這篇文章裡,我會用「知識的生命週期」這個維度去介紹這個願景。

知識的生命週期

要打造一個脈絡化的知識網路,第一件事情是要確保生命週期中所有環節的資訊都能被互相使用。當前軟體世界針對此問題的解法有兩個大方向。

第一個方向是提高單一軟體的能力,常見做法是在一個軟體中塞入大量功能(例:Notion),或是針對不同場景去擴充特定的功能插件(例:Obsidian),滿足盡可能多地使用場景。這類做法最常見的缺點是使得軟體的學習曲線變得非常陡峭、易用性大幅下降,資源的分散導致單點功能無法做到特別突出,而無止盡的擴充插件也容易變得難以管理和維護。

第二個方向是透過 API(可能來自不同軟體,也可能是 File System 原生提供)來整合多個軟體的資訊。這是當今世界在整合不同軟體能力時最常見的做法,然而這個做法需要極高的開發和維護成本,並且需要在不同軟體之間資料格式的相容性和同步上做出非常多取捨。若不同軟體之間的資料是用複製的方式在整合的,那麼你終究很難真的獲得「在一個軟體中使用另一個軟體」的整合式體驗;但若不同的軟體在缺乏某種通用協議的前提下去共用資料庫,那麼資料毀損的風險就會隨著軟體數量而指數提升。

我們是否一定要在上述這二大方向之間做出妥協呢?在經過一番思考後,我認為若想打造符合我們願景的脈絡化知識網�路,這個網路必須滿足三大原則:第一,所有軟體必須共用相同的資料格式。第二,所有軟體必須遵守一套資料處理原則的通用協議。第三,軟體必須盡可能地與資料解耦,避免直接擁有資料。Heptabase 就是基於這三個原則打造的一個系統。

在我所構想的這個系統裡頭,所有的資料都是「卡片」。卡片可以被擴充成非常多種類型,它可以是筆記、PDF、影音、圖片、電子書、表格、…… 這些基本類型,也可以是化合物、基因序列、藥物、演算法、…… 這些專業領域中的特殊資料物件。所有的卡片都會以一種通用的資料格式來保存它的 metadata,而在這個系統上所有的、我稱之為 Meta App 的軟體會以一種通用的協議來調用和編輯這些 metadata。如此ㄧ來,每個 Meta App 都可以維持自身的易用性,而 Heptabase 作爲乘載這些 Meta App 的作業系統以及開啟 Meta App 和卡片的瀏覽器,既可以確保資料在 Meta App 之間是通用的、免去在它們之間串接資料的成本,也可以透過建立 metadata 的抽象層將資料和 Meta App 解耦,讓我們在確保所有 Meta App 在共用相同資料格式的同時,大幅降低資料被 Meta App 的開發者毀損的風險。

脈絡的回溯

要打造一個脈絡化的知識網路,第二件事情是要確保所有知識和想法背後的思考脈絡都能被完整保存和追蹤。當你看到一個想法時,你必須能回憶起這個想法是怎麼產生的、又在哪些場景下被使用。

人類創造出的所有知識和想法,都是先有輸入,才有輸出。「追蹤思考脈絡」其實就是在幫助我們暸解什麼樣的輸入造成了什麼樣的�輸出。也因此,我們必需打通生命週期中的「收集」、「思考」、「創作」這三個環節。

收集環節的原則是「快」。想法總是一閃即逝的,好的收集工具應有非常低的阻力,在想法產生的當下就能將其捕捉。在 Heptabase 裏,負責這項任務的 Meta App 叫 Journal。你隨時打開就可以將想法直接倒入,連創建筆記都不需要。

思考、創作環節的原則是「視覺」。人的思維架構通常都是在視覺化後才得以明瞭,在空間中移動和重組資訊更是輔助思考的重要程序。在 Heptabase 裏,負責這項任務的 Meta App 叫 Whiteboard。你可以將 Journal 的資訊拖曳到無限的白板空間上製作卡片,並透過卡片的排版來釐清思維架構。一張卡片可以同時出現在多個白板裡頭。

Journal 和 Whiteboard 作為 Meta App 並不擁有卡片的資料,而是會去引用 Heptabase 的卡片資料庫。它們唯一會擁有的資料,只有一些在呈現卡片機制上需要用的 metadata。舉例來說,Whiteboard 不直接擁有卡片內容,但是會存取卡片 Id 在不同白板裡的空間屬性(形�狀、顏色、箭頭)。

這種共享資料庫的作法能確保每個 Meta App 都不過於複雜,但又能很好地整合成一個工作流,避免資訊在不同環節間產生無法追蹤的斷層。當你看到一張卡片時,你既可以追蹤它被創建的時間、它被哪些其他卡片給提及,亦可以追蹤它出現在哪些白板裡頭、處在哪一些思維架構中的什麼位置。

集體知識的創建

要打造一個脈絡化的知識網路,最後一步是讓不同的個體思考能互相激盪,進而讓集體智慧浮現,產出任何人都無法單靠自己創造出的知識。這裡必需打通的是生命週期中的「分享」、「探索」環節。

提到集體智慧,我們第一個聯想到的軟體往往是 Notion、Miro 這類提倡「共同工作區」和「即時協作」的產品。然而,這類產品往往有以下三大問題,讓集體智慧不易浮現。

第一,它們自上而下地強迫大家使用一套相同的資訊架構來整理資訊,而不是讓每個人使用真正適合自己的資訊架構。

第二,每個人的思考狀態互相重疊在同個工作區,容易造成資訊系統的紊亂。你很難知道哪些文檔已經過期了,哪些則還在使用。一份協作文檔如果被很多人編輯過,你也難以追蹤每個人編輯的理由和背後的思考脈絡。

第三,在想法尚未成熟時就進入即時協作狀態,容易造成群體盲思,不利於獨立思考。基於效率考量,協作通常會採多數決的方式去發展想法,導致個人的獨特想法無從表達、受到壓抑,在最初期就被扼殺。

在 Heptabase,我們提倡的是以「個人工作區」為基礎,自下而上的「非同步分享」。當知識工作者們要協作時,他們可以以個人工作區出發去做非同步分享,在不打擾彼此思緒、不犧牲獨立思考的前提下,更好地去追蹤其他人的想法、復用彼此的知識。

人們不再只能分享零散的想法,而是能分享以想法為單位構成的思維架構。每個思維架構中的每個想法,都可以被其他思維架構使用,而 Heptabase 的脈絡追蹤機制將允許你以想法為起點去探索所有使用到特定想法的思維架構。

總結

總結來說,在「知識的生命週期」這個維度上,我們希望能透過 Heptabase 的工具來幫助全世界的知識工作者打通「探索 → 收集 → 思考 → 創作 → 分享」的知識生命週期,讓資訊具備原生的互用性、讓想法的脈絡可被追蹤、讓集體知識的創建更為容易,進而演化出一個脈絡化的知識網路。

在下一篇文章,我將深入介紹 Heptabase 這個系統的結構,以及我們迭代這個系統的路線圖。