01 - The Context

- English

- 中文

This article was published on June 29, 2020 by Alan Chan, co-founder of Heptabase, while he was still in college. It was written two years before he started building the early-alpha Heptabase.

Foreword

During my gap years, I spent a lot of time thinking: What do I want to do with my life? At the end of the two years, I compiled a list of three things, based on the time scale:

- Short-term: To accelerate the speed of the human’s intellectual and technological progress to the theoretical limit.

- Medium-term: To develop a humane way of integrating our mind and body with technology to help humanity reach a higher level of intelligence, capabilities, and life form.

- Long-term: To ensure that the order of the observable universe will not come to an end in the future because of Physics limitations and that the order will continue and evolve forever.

For me, at this moment, the first thing is the most important. It is the foundation needed to achieve the second and third things, and it’s also my vision for the world in the next 10 years. Having solved the “What” question, the next step is to figure out “How.” In other words, having a vision is not enough. I must have a clear goal for the world 10 years from now so that I know in which direction I can work on. This is exactly what I had been thinking about and researching in the past year.

Now a year has passed, and my goal has never been clearer. However, I found that although I could explain my goal in one sentence, in the absence of context, it was difficult for others to understand its value and importance immediately. This is mainly because my goal involves many dimensions, and to see the whole, you have to look at all dimensions at the same time. The linear structure of the language only allowed me to describe one dimension at a time, which had limited my ability to completely explain the goal.

That doesn’t mean I shouldn’t spend time explaining what I’m doing. As Richard Hamming said in his You and Your Research talk:

It is not sufficient to do a job, you have to sell it. You must present it so well that they will set aside what they are doing, look at what you’ve done, read it, and come back and say, “Yes, that was good.”

So I decided to start writing a new series. This series is my attempt to explain my goal in a more systematic way. It’s also a personal public statement. Although I’ve had this goal for a long time, the goal is harder than anything I’ve done in my life so far, and it wasn’t until the last few months that I felt confident enough to be able to challenge it. Because it’s very hard, in the next few years, I will face many moments that will make me want to give up. Hence I decided to publicly state what I want to accomplish in the next few years to avoid using excuses and giving up in the future.

In this series, I will focus on one dimension of my goal in each article. The dimension that this article addresses is the historical context behind my goal. I’ll start by briefly sharing the research I did for achieving my vision, then explain how the research process had made me interested in computer history, and finally discuss how I derived my goal based on my past research and my understanding of computer history. If you’re interested in this, I recommend you to read The Dream Machine by Mitchell Waldrop or The Innovators by Walter Isaacson.

The Road to the Vision

To translate the vision of “To accelerate the speed of the human’s intellectual and technological progress to the theoretical limit” into a concrete goal, I think the most important aspects to consider are “Optimizing the methods of human knowledge creation” and “Optimizing the tools of human knowledge creation”.

The first aspect is “Optimizing the methods of human knowledge creation,” which I think can be broken down into two main problems:

- What way of thinking creates better knowledge?

- How can we make as many people as possible think this way?

To answer the first question, here are some worthwhile starting points: philosophy of science, epistemology, psychology, the study of productivity, and so on. What philosophy of science and epistemology discussed is exactly the problem of “how do people create knowledge”, among which I found Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and Popper’s Evolutionary Epistemology particularly inspiring. Psychology is important because, in order to find the best way to create knowledge, we must first understand how humans think and how memory works. The study on productivity, such as GTD and Zettelkasten Method, can help us see the possibility of improving the efficiency of human knowledge creation from a more practical perspective. These are some of my main research directions in the first half of 2019.

To answer the second question, I decided to study at Minerva Schools. Minerva’s education emphasizes “learning how to think” over “learning knowledge,” and what we did throughout the freshmen year was to learn the Habits of Mind and Foundational Concepts that are common across different disciplines. I believe once we figure out how to spread this kind of education around the world, it will contribute a lot to accelerating the speed of human knowledge creation. On the other hand, I am constantly researching how to use different existing platforms and media to spread ideas, such as Medium, Facebook, Twitter, Blogger, Gmail, Goodreads, Youtube, podcasts, and so on. This study of platforms and media is indispensable if I want to popularize important methods related to “creating knowledge” in the future.

Then there is the aspect of “Optimizing the tools of human knowledge creation,” which I think can also be broken down into two main problems:

- How can tools augment one’s intellectual activities?

- How can tools augment intellectual activities among multiple people?

For the first problem, I was most inspired by Notion, a digital workspace that allows you to organize, manipulate, and create all kinds of information very efficiently. Notion supports almost any data format you can think of; you can easily drag and drop these data blocks to set the views and create links between pages at any time to build your own knowledge network. Although Notion, as a team project management product, is not good at handling complex research knowledge work, the way it approaches data has shown me many new possibilities.

For the second problem, I was most inspired by Dynamicland, a research center in Oakland. People here believe that to create great ideas, we must first have a good “medium of thought”. For example, when two people are discussing, the medium is sound; when two people are drawing together, the medium is paper. The limitation of sound is its unidirectional linear structure, while the limitation of the paper is its static nature. According to Dynamicland’s researchers, the essence of a computer is not the keyboard, mouse, and screen, but computation and interaction. If we think of the computer as a “dynamic medium” and carefully redesign the way it communicates with people, we might be able to unlock the full potential of “computation” and “interaction”, and use this medium to create powerful ideas that can’t exist in sound or paper. So in Dynamicland, the computer is not a machine on the table, but a space full of projectors and cameras where you and your friends can manipulate objects to express, communicate, and even create new ideas.

To sum up, to achieve the vision of “To accelerate the speed of the human’s intellectual and technological progress to the theoretical limit,” I had spent the past year focusing on the philosophy of science, epistemology, psychology, productivity, education, media, design, and human-computer interaction to deepen my understanding of the methods and tools for creating knowledge. After some research, I realized that although I started with methods and tools as two different aspects, there was a co-evolution relationship between them. The progress of tools will lead to the paradigm shift of methods, which in turn will affect tool design and requirements. Minerva’s approach to education, for example, owes much to Forum, the software Minerva developed for teaching. Many of the productivity methods mentioned earlier also require good tools to implement, such as Notion and Roam. In other words, once you incorporate a certain method and philosophy of doing things into the design of the tools, when you popularize the tools, you also popularize the methods and philosophy. It’s very much like how language works. If our language doesn’t have words like “if,” “why,” and “value,” we’re losing a set of thinking tools for making assumptions, asking questions, and making decisions. Just imagine how much it could affect the way we think!

After understanding the co-evolution between methods and tools, I began to think more seriously about which aspect I could have more contribution. I found that if I decide to directly reform the education system, not only is the speed of iteration and scaling slow, but the time between making the reform and seeing the effect is also longer, and the problems I will face in the process will be more political. On the other hand, tools iterate and scale faster, the cost is lower, the effect can be seen immediately when people start using the tool, and the problems I will face are more about design and engineering, which are both things I’m good at. So by the end of 2019, I gradually switched my focus on the tools aspect. I wanted to know how organizations like Notion and Dynamicland created tools that augment human intellectual activity.

After gathering tons of information from the internet and actually talking to people who work in Notion and Dynamicland, I realized that the goals of these two organizations are to fulfill the vision of computer pioneers from the 1960s. For example, the biggest inspiration for Notion is Douglas Engelbart, who was the pioneer of modern computers, the internet, and human-computer interaction in the 1960s. He even wrote a paper called Augmenting human intellect: A conceptual framework, which topic is exactly about how to use tools to augment human intellectual activities. On the other hand, I also found that Alan Kay, the co-founder of the Communications Design Group (CDG), the predecessor of Dynamicland, was arguably the father of the personal computer. Without Alan Kay, who pioneered a number of breakthroughs in personal computing with his team, the modern world of technology would have gone straight back 30 years.

This understanding has led me to realize that organizations like Notion and Dynamicland didn’t invent amazing tools and research out of thin air. Their works are based on certain historical contexts, and they have inherited the ambition of the pioneers. So I started to devote a lot of time to the computer history with the hope of getting some inspiration to help me achieve my vision.

Computer History

History is never a single thread. It is made up of many different threads and branches. The computer history is the same: it is not only about computers, but also about the important developments of the twentieth century in many different fields, such as mathematics, philosophy, politics, psychology, neuroscience, artificial intelligence, electrical engineering, and the technology industry. It was this interplay and stimulation between different fields that had created the technological world we know today. If we dig into computer history, we will find that many important people came from different fields. These people were exposed to each other’s ideas by chance, but then built their works on the ideas and foundations of those who came before them as if they were destined to do so.

For example, if mathematician Gödel had not come up with the famous Gödel Incomplete theorem, Alan Turing, the father of computers, would not have been motivated in the 1930s to design a machine that could simulate the thinking of a mathematician, much less invented the concept of a general-purpose computer. Had it not been for the huge numerical calculations required to build the atomic bomb in World War II, von Neumann would not have had an incentive to get involved in computing in the 1940s, much less invented the hardware architecture that underlies all modern computers. Without the contributions of Turing and von Neumann, computer science would have lacked a foundation, and many of the technologies we know would not have existed.

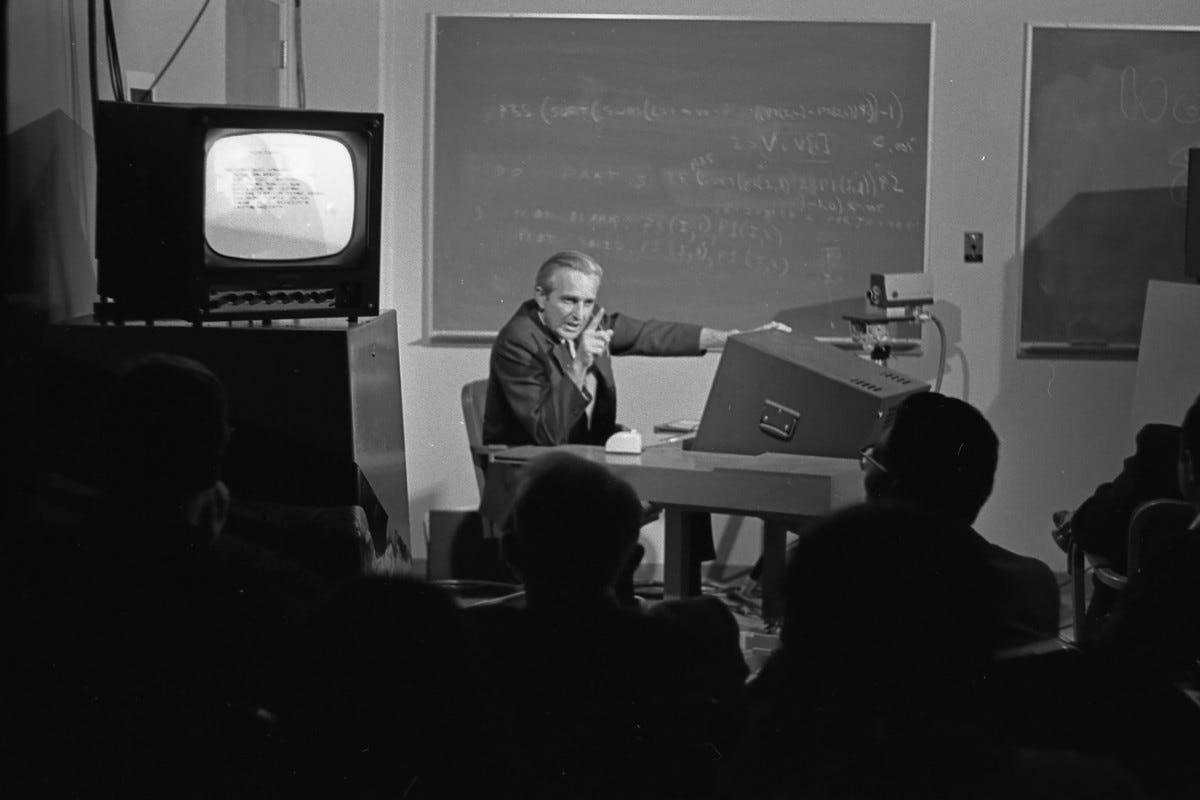

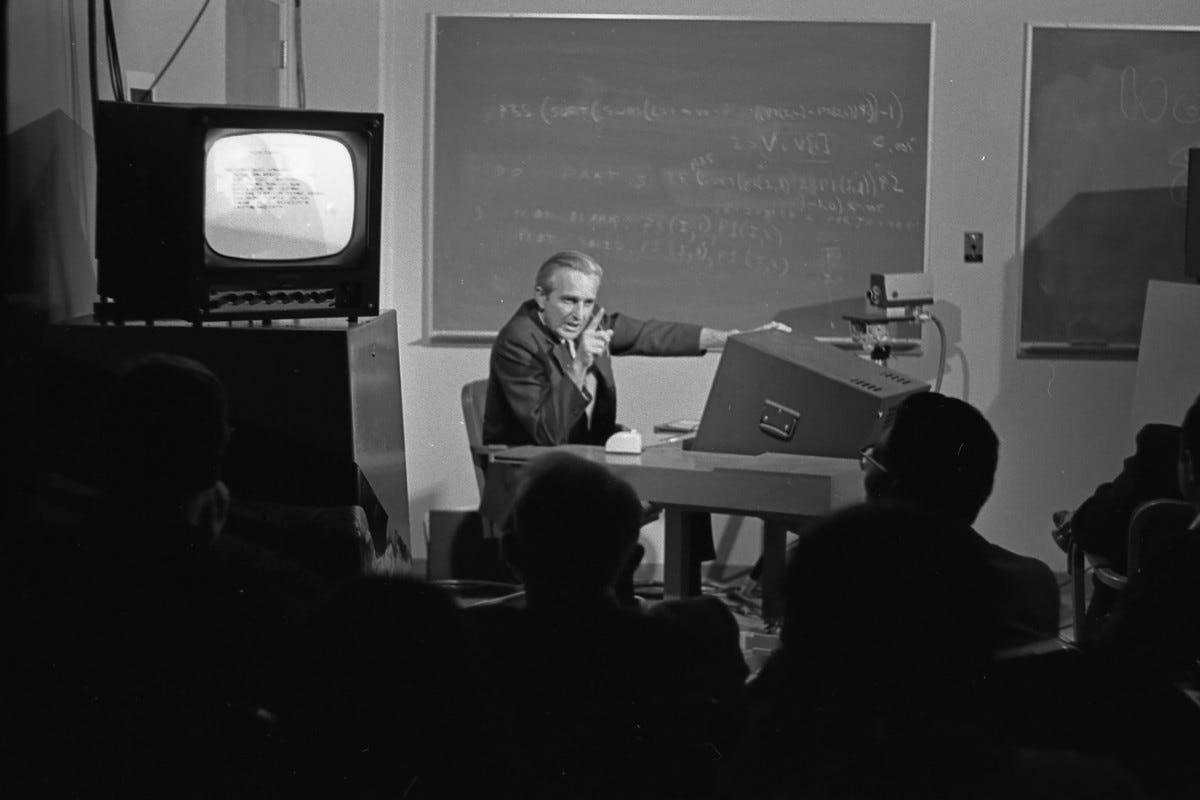

On the other hand, if Claude Shannon and Norbert Weiner had not pioneered Information Theory and Cybernetics Worldview in the 1940s, George Miller was unlikely to have made a Cognitive revolution that shifted the psychological paradigm away from the Behaviorism of the 1960s to the current Cognitive Science. Nor was it likely that J.C.R. Licklider, a psychologist who worked with Miller, came up with the idea of Man-Computer Symbiosis. Computers might still be cold military machines housed in large warehouses. And If Eisenhower, the President of the United States, had not established ARPA in the face of Soviet competition, and if the first director of ARPA had not hired Licklider as the director of the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO), Licklider would not have been able to sponsor so many important research on computers and artificial intelligence across the country. Without Licklider’s sponsorship, Douglas Engelbart, the aforementioned pioneer of human-computer interaction, would not have been able to build the NLS system that shocked the world with The Mother of All Demos in 1968.

Similarly, if Engelbart had not publicly revealed the limitless potential of computers by the demo of the NLS system, people like Alan Kay might not have been so impressed and inspired to gather in Xerox PARC in the 1970s and make groundbreaking breakthroughs that went far beyond their era, such as personal computers, object-oriented programming, Graphical User Interface, Ethernet and other revolutionary technologies. Without the technological achievements of Xerox PARC, there’s no way that people like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates could have introduced personal computers with Mac OS and Windows in the 1980s, and Apple and Microsoft probably would not become dominant tech companies in the modern era.

“Why hasn’t this company brought this to market?” Jobs famously shouted, waving his arms around while his engineers did their best to ignore him and focus on how the system worked. “What’s going on here? I don’t get it!” By the time the Apple team finally departed Xerox PARC, according to Jobs’s later account, he was a “raving maniac”: he had seen the future.

The Xerox Thieves: Steve Jobs & Bill Gates

They met in Jobs’s conference room, where Gates found himself surrounded by ten Apple employees who were eager to watch their boss assail him. Jobs didn’t disappoint his troops. “You’re ripping us off!” he shouted. “I trusted you, and now you’re stealing from us!” Hertzfeld recalled that Gates just sat there coolly, looking Steve in the eye, before hurling back, in his squeaky voice, what became a classic zinger. “Well, Steve, I think there’s more than one way of looking at it. I think it’s more like we both had this rich neighbor named Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set and found out that you had already stolen it.”

As Xerox PARC dissolved, its members went their separate ways and made significant contributions to the technology community: Bob Metcalfe founded 3Com, John Warnock and Charles Geschke founded Adobe, Bob Belleville went to Apple to manage the Macintosh software team, and Charles Simonyi joined Microsoft and helped create Microsoft Word. Thanks to these ubiquitous efforts, coupled with the popularity of personal computers, the modern online world has been able to thrive, enabling the rise of new tech giants like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Netflix.

How to make great Contributions

Looking back at the entire history of computers, we can see that history, at some level, is determined by a large number of contingencies. However, despite such randomness, many of the great events in history had occurred according to a common set of laws: no matter how great a person was, he/she must face the limitations of his/her time. Leonardo da Vinci couldn’t have invented a smartphone in his day because the technology wasn’t there yet; Galileo couldn’t have discovered general relativity in his day because the mathematics for it had not yet appeared. And those who did make great contributions were great not just because they were good at what they did, but because they knew where they were in history and how to put what they think is important in that position to move it forward. This allowed them to make great contributions in the right place at the right time.

It’s never easy to make a great contribution in the right place at the right time. There were more ideas in the world that, though great, were difficult to put into practice when they were first proposed and couldn’t contribute to the world immediately because of the limitations of their era. For example, in the field of artificial intelligence, the concept of Neural Networks was proposed by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts as early as the 1940s. However, it was not until the 2010s, when GPU hardware was mature and the rapid development of the Internet had accumulated tons of data, that neural networks could exert their influence. Another example is in the 1930s, when Vannevar Bush proposed Memex, an information system based on “association” and broke the linear structure of books, in his famous article As We May Think. But it was not until the 1980s when personal computers became ubiquitous and information transmission technology was in place, that the hyperlink-based World Wide Web was finally developed.

The above examples have shown a way in which we can make great contributions: Looking back at the important ideas in history, which ideas weren’t practical then, but are now becoming feasible? This is what Notion and Dynamicland are doing right now. This is one of the reasons why interdisciplinary knowledge is important: history is a multi-line interwoven. Just look at the people who had come up with great ideas in computer history. Von Neumann, Norbert Weiner, and Alan Turing were mathematicians, J.C.R. Licklider was a psychologist, Alan Kay was a biology major and Steve Jobs was a businessman. If one only knows how to write code and has no perspective from other fields, it is easy to fall into the bottleneck of mainstream thinking without seeing the overall context of history, let alone identifying the important ideas.

After acquiring such understanding, I realized: if I want to achieve my vision, not only do I need interdisciplinary knowledge, I also need to pay attention to the historical context, to figure out what position are we in the history and how can I put what I think is important in this position to move the history forward and build the future world that I envisioned.

Goal

After understanding the importance of history, I began to spend time researching some of the early works by computer pioneers such as J.C.R. Licklider, Douglas Engelbart, Alan Kay, Ted Nelson, as well as articles and videos by modern experts working in similar directions such as Bret Victor, Andy Matuschak, and Michael Nielsen. Among them, what influenced me the most was Augmenting human intellect: A conceptual framework by Engelbart in 1962, and many videos and articles on his official website.

Surprisingly, I found I’ve already thought about many of Engelbart’s ideas over the past three years or have been exposed to similar ideas in other books and courses. What Engelbart’s paper did, was that it put everything together in a systematic way, which to me was like putting glasses on a person with myopia, and suddenly the world became crystal clear. From this newly-gained perspective, what Notion and Dynamicland are doing now totally makes sense to me.

Certainly, Notion and Dynamicland are not the only tools that augment human intellectual activities. There are many other different tools such as Roam, Muse, Figma, Are.na, Hypothes.is, etc. So for me, in addition to figuring out where I am in history and identifying the important ideas that are becoming feasible in modern times, it’s also important to look at the different people and projects scattered around the world. What have these people done with these ideas? What kind of success have they achieved? What kind of dilemma are they facing? All of this information is extremely valuable to me.

At this very moment, I have found the direction that I think is extremely important for the human world in the path of “augmenting human intellectual activities through tools.” I’m pretty sure this is something worth working on for a long time, not just because it’s an idea that was proposed by the pioneers and now becoming feasible, but what’s more important is if I don’t do it, someone will. But in this direction, everyone else is doing it wrong, and only I know how to do it right. I’ve been thinking about it for three years, and I’m convinced that the world needs me to do this.

My goal for the next ten years is to design and build a truly universal Open Hyperdocument System and build on that system the next generation of the Internet.

這篇文章是由 Heptabase 的共同創辦人詹雨安於 2020 年 6 月 29 日發布。當時他仍在讀大學,距離 Heptabase 推出早期 Alpha 版本還有二年。

前言

在休學的兩年期間,我花了很多時間在思考「我這一生想要做的事情是什麼?」在兩年的最後,我根據時間的尺度,整理出了以下三件希望在有生之年做到的事情:

- 短期:將整個世界知識與技術增長的速度優化到理論極限。

- 中期:發展出一種人性化的方式使人類與科技完全融合,提高人類在智力、能力和生命形式上的水平。

- 長期:使可觀測宇宙的秩序得以永遠延續、不斷升級,不會因為物理學的限制而走入終點。

在這三件事情中,對當下的我來說,第一件事情是最為重要的,它是要達成第二、三件事情所需要的基礎,表達的是「我對世界未來十年的願景」。搞清楚了「做什麼」的問題後,下一步就是要搞清楚「如何做」,因此我必須為十年後的世界建立一個清晰的目標,才知道我可以往什麼樣的方向努力。這正是我過去一年主要思考和研究的方向。

一年過去了,如今我的目標已經變得前所未有地清晰。然而,我發現雖然我可以用一句話闡述我的目標,但是在缺乏脈絡的情況下,別人很難在短時間內暸解它的價值和重要性。這主要是因為這個目標涉及了很多維度,要看清楚它的整體,就必須把所有的維度放在一起看。語言的線性結構使得我一次只能描述一個維度,在表達上有所限制。

這並不代表我不該花時間好好解釋我在做的事情。正如 Richard Hamming 在 You and Your Research 的演講中所說:

光是做完工作還不夠,你還得把它推銷出去。你必須要好好的報告你的成果,讓人們放下手邊的事,專心的看你做出的東西,閱讀它,然後回來說「沒錯,這東西的確有價值。」

因此我決定開始寫一個新的系列文,這個系列是我對於「用一種更系統的方式傳達我的目標」所做的嘗試。同時,它也是一個屬於我個人的公開聲明。雖然我已經擁有這樣的目標很長一段時間了,但對我來說,這個目標比我人生至今做的每一件事情都還困難,一直到過去幾個月我才有足夠的信心確定我有能力挑戰它。而正是因為它很困難,在未來的幾年內我一定會面臨很多想要放棄的時刻,所以我希望透過在網路上公開聲明我在接下來幾年要完成的事情,讓未來的我失去放棄的藉口。

在這系列的每一篇文章中,我都會著重在關於我的目標的其中一個維度,把這個維度好好講清楚。而這篇文章作為開篇,著重的維度就是我的目標背後的歷史脈絡。我首先會分享我為了實現願景所做的研究,接著解釋這個研究的過程如何讓我對計算機的歷史產生興趣,最後談我如何根據我過去的研究和我對計算機歷史的理解,導出具體的目標。對於這段歷史如果有興趣,可以參考 Mitchell Waldrop 寫的 The Dream Machine 或是 Walter Isaacson 寫的 The Innovators。

通往願景的道路

對於「將整個世界知識與技術增長的速度優化到理論極限」這個願景,要把它轉換成具體的目標,我認為需要考慮的最重要的面向有兩個:「優化人類創造知識的方法」、「優化人類創造知識的工具」。

首先是「優化人類創造知識的方法」這個面向,我認為可以拆分成兩個主要問題:

- 什麼樣的思考方式能創造出更好的知識?

- 如何讓盡可能多的人學會這樣的思考方式?

要回答第一個問題,以下是一些值得出發的起點:科學哲學、認識論、心理學、生產力的研究等。科學哲學和認識論所討論的正是人們創造知識的方式,其中我覺得特別具有啟發性的,包含了 Kuhn 的科學革命的結構(The Structure of Scientific Revolutions)和 Popper 的進化認識論(Evolutionary epistemology);心理學之所以重要,是因為若想找出創造知識的最佳途徑,首先我們必須得暸解人類是如何思考、人腦的記憶是如何運作的;而諸如 GTD、Zettelkasten Method 等有關生產力的研究,則能從更實務的面向,讓我們看到提升人類創造知識效率的可能性。這些都是我在 2019 上半年主要的研究方向。

對於第二個問題,它構成了我選擇來 Minerva 大學就讀的其中一個重要原因。Minerva 的教育強調「學習如何思考」大過「學習知識」,而大一整年在做的事情,正是訓練學生熟悉不同科系和領域中共同存在的思維習慣與基礎概念(Habits of Mind and Foundational Concepts)。我認為一但能找出將這種教育普及世界的方式,對於提升人類創造知識的速度將會有非常大的助力。另一方面,我也不斷地在研究如何利用不同的現有平台和媒介傳播思想,例如 Medium、Facebook、Twitter、Blogger、Gmail、Goodreads、Youtube 和 Podcast 等等。如果我想在未來普及與「創造知識」有關的重要方法,這種對平台和媒介的研究是不可或缺的。

再來是「優化人類創造知識的工具」這個面向,我認為也可以拆分成兩個主要問題:

- 如何透過工具強化一個人的智力活動?

- 如何透過工具強化多個人共同進行的智力活動?

對於第一個問題,最讓我受到啟發的是 Notion,一個能讓你非常高效地整理、操控和創造各類資訊的數位空間。Notion 支援了幾乎所有你想得到的資料格式,你在輸入這些資料格式的同時,還能輕易地透過拖拉來調整排版,並且能隨時在不同的頁面之間建立連結,打造屬於自己的知識網絡。雖然 Notion 為團隊專案協作所設計的產品介面並不適合處理複雜的知識研究,但它看待資料的方式讓我看到了很多新的可能性。

對於第二個問題,最讓我受到啟發的是 Dynamicland,一個在 Oakland 的研究中心。這裡的人認為,要創造出偉大的想法,首先必須要有好的「思想媒介」。舉例來說,兩個人在討論事情時,這個媒介就是聲音;兩個人一起在紙上畫畫時,這個媒介就是紙張。聲音的局限在於它的單向線性結構,而紙張的局限在於它的靜態性。Dynamicland 的研究員認為,電腦的本質並不是鍵盤、滑鼠和螢幕,而是計算和互動。如果我們將電腦視為一種「動態媒介」,並善加設計這個媒介與人之間溝通的方式,我們將有辦法完全釋放「計算」和「互動」的潛能,在這個媒介上創造出我們無法透過口語或紙張創造出的強大思想。所以在 Dynamicland 裡,「電腦」不是一部機器,而是一個充滿著投影機和攝影機的「空間」,你和你朋友可以透過操縱空間中的物件來表達、溝通甚至是創造新的思想。

總體而言,為了達成「將整個世界知識與技術增長的速度優化到理論極限」這個願景,我過去一年多的時間主要聚焦在科學哲學、認識論、心理學、生產力、教育、媒體、設計和人機互動等領域,目的正是為了加深我對創造知識的方法和工具的理解。在一番研究之下,我意識到,雖然我一開始將方法和工具視為兩個不同的面向,但它們之間其實存在著相互演化的關係。工具的進步會造成方法的範式遷移,方法的範式遷移又會反過來影響工具的設計和需求。舉例來說,Minerva 的教育方法要有成效,很大程度上得歸功於它所開發的 Forum 這個授課軟體;而前面所提及的許多生產力的方法,也需要有像 Notion、Roam 這樣的良好工具才得以完整實現。換句話說,一旦你將某種做事的方法和哲學融入到工具的設計,那麼當你在普及工具時,也等於是普及了這些方法和哲學。這點跟語言很像。如果我們的語言沒有「如果」、「為什麼」、「價值」等詞彙,我們就等同於失去了一套進行假設、提出問題和做出選擇的思考工具,這對我們的思考方式會產生多大的影響,相信我不需要多作解釋。

暸解到方法和工具之間相互演化的關係後,我開始更認真地思考我在哪個面向上能產生更大的貢獻。我發現,如果我想直接從教育方面推動改革,不僅迭代和規模化的速度較慢,從做出改革到看到效果之間的時間間隔也較長,且在過程中會面對的問題更多時候是政治問題。反過來看,工具迭代和規模化的速度快、成本低,使用工具的當下馬上就能看到效果,會遇到的問題更多是設計問題和工程問題,剛好都是我比較擅長的領域。所以我在 2019 年底時,便逐漸把我的專注更多地放到工具這個面向上。我想知道像 Notion 和 Dynamicland 這樣的組織,是如何打造強化智力活動的工具的。

在透過網路搜尋大量資料,並實際與 Notion 和 Dynamicland 的人交流過以後,我發現這兩個組織的目標都是希望完成 1960 年代計算機先驅們的願景。舉例來說,啟發 Notion 最大的計算機先驅是 Douglas Engelbart,他是 1960 年代開發計算機、網路和人機互動的先驅,還寫過一篇叫 Augmenting human intellect: A conceptual framework 的論文,談的主題正是如何用工具來強化人類智能。另一方面,Dynamicland 的前身、CDG 研究中心的共同創辦人 Alan Kay,可以說是個人電腦的鼻祖。如果沒有 Alan Kay 與他的團隊在個人電腦領域作出大量開創性突破,現代的科技世界可能會直接倒退三十年。

在有了這樣的認識之後,我才暸解到,像 Notion 和 Dynamicland 這樣的組織,之所以能做出驚為天人的產品和研究,靠的並不是憑空蠻幹,更多是因為他們背後承襲著某個歷史脈絡。這使得我開始投注大量的時間,關注計算機發展的歷史,希望能從中獲得一點啟發,幫助我達成我的願景。

計算機歷史

歷史從來都不會只有單一主線,而是由許多不同的主線和支線交織而成的。計算機的歷史也一樣:它不只跟計算機有關,也牽涉到了許多不同領域在二十世紀的重要發展,像是數學、哲學、政治、心理學、神經科學、人工智慧、電子工程、科技產業等。正是這種不同領域之間的相互影響與刺激,才造就了我們如今所熟悉的科技世界。如果深入去看計算機的歷史,我們會發現在這段歷史中的重要人物,很多都來自不同領域。這些人在偶然的情況下才接觸到彼此的思想,又如同必然般,不斷地在前人的想法和基礎上做出貢獻。

舉例來說,如果數學家 Gödel 沒有提出著名的 Gödel 不完備定理,計算機之父 Alan Turing 在 1930 年代時就不會有動機想要設計出能模擬數學家思考的機器,更不太可能發明出通用計算機的概念。如果不是因為二戰製造原子彈的過程需要龐大的數值計算,von Neumann 在 1940 年代時就不會有動機涉足計算機領域,更不太可能發展出所有現代計算機底層使用的硬體架構。如果沒有 Turing 和 von Neumann 的貢獻,計算機科學就會缺乏基礎,許多我們熟知的科技也不太可能發生。

另一方面,如果 Claude Shannon 和 Norbert Weiner 沒有在 1940 年代開創出資訊理論(Information Theory)和控制論世界觀(Cybernetics Worldview),George Miller 就不太可能做出認知革命、將心理學的範式從 1960 年代的行為主義(Behaviorism)轉移到現代的認知神經科學(Cognitive Science);曾與 Miller 共事過的心理學家 J.C.R. Licklider 也不太可能構想出人機共生(Man-Computer Symbiosis)的想法,計算機至今可能仍是冷冰冰的、關在大型倉庫裡的軍用機器。而如果當時的美國總統 Eisenhower 沒有在面對蘇聯競爭壓力的情況下成立 ARPA,且如果 ARPA 的第一任局長沒有聘用 Licklider 為 ARPA 旗下信息處理技術辦公室 (Information Processing Techniques Office)的主管,Licklider 就不會有錢贊助遍佈全國、有關電腦與人工智慧的重要研究。如果沒有 Licklider 的贊助,前面提到的人機互動先驅 Douglas Engelbart 就不太可能打造出 NLS 系統,並在 1968 年用 The Mother of All Demos 震撼世界。

同樣地,如果 Engelbart 當年沒有在公開場合用 NLS 系統揭示計算機的無窮潛力,諸如 Alan Kay 等人可能就不會受到震撼與啟發,並於 1970 年代聚集在 Xerox PARC 做出遠超當代的開創性突破,創造出個人電腦、物件導向程式語言(Object-oriented Programming)、圖像化介面(Graphical User Interface)、乙太網路(Ethernet)等眾多革命性技術。而如果沒有 Xerox PARC 的技術成果,我們熟知的 Steve Jobs 和 Bill Gates 等人就不可能在 1980 年代推出裝載 Mac OS 和 Windows 的個人電腦,Apple 和 Microsoft 很可能也無法成為統治當代的科技公司。

「為什麼這家公司沒有將它推向市場?」賈伯斯揮舞著手臂大叫,而他的工程師們竭盡全力不理他,而是專注在研究系統的運作方式。 「這到底是怎麼一會事?我不懂!」根據賈伯斯後來的說法,當蘋果團隊最終離開 Xerox PARC 時,他是個「瘋狂的瘋子」:他看到了未來。

The Xerox Thieves: Steve Jobs & Bill Gates

蓋茲在賈伯斯的會議室,十位蘋果員工等在一旁,準備看老闆發飆。賈伯斯沒讓他的手下失望。賈伯斯大吼:「你這個不要臉的小偷!我信任你,你卻從我們這裡偷東西!」何茲菲德記得蓋茲只是冷靜坐著,直視賈伯斯的眼睛,久久才用粗嘎的嗓音說道:「史帝夫,我想我們應該從另一個角度來看這件事。你我都是 Xerox PARC 的鄰居。有一天,我闖入這個有錢鄰居的家,打算偷走電視機,發現你已經捷足先登。」

隨著 Xerox PARC 逐漸解散,PARC 的成員也各奔東西,各自在科技圈發揚光大、做出龐大貢獻:Bob Metcalfe 成立了 3Com、John Warnock 和 Charles Geschke 成立了 Adobe、Bob Belleville 到 Apple 管理 Macintosh 的軟體團隊、Charles Simonyi 加入 Microsoft 並幫助創造了 Microsoft Word。正是因為有這些遍佈各地的成果,搭配個人電腦的普及,現代的網路世界才有辦法蓬勃發展,讓 Google、Facebook、Amazon、Netflix 等新興科技巨頭得以崛起。

如何做出卓越貢獻

快速回顧整段計算機歷史,我們可以發現,歷史在某種層面上,是由大量的偶然事件所決定的。然而即便歷史充滿偶然,許多歷史中的偉大事件之所以會發生,其實仍遵循著一套共同的規律:再怎麼厲害的人物,都必須面臨時代的限制。達文西在他的時代不可能發明智慧型手機,因為相應的技術還不到位;伽利略在他的時代也不可能發現廣義相對論,因為相應的數學還沒出現。而那些能做出卓越貢獻的人之所以偉大,並不只是因為他們能力出眾,更是因為他們知道自己處在歷史中的什麼位置,並知道如何在這個位置中加入他們認為重要的元素,使歷史往前推進一步。這使得他們得以在正確的時間點,正確的地方,做出卓越的貢獻。

在正確的時間點做出卓越的貢獻,要做到這件事情絕對不容易。這世界上存在更多的,是那些雖然偉大,但在剛被提出時因為時空背景的限制而難以被實踐、無法立即對世界產生貢獻的想法。舉例來說,在人工智慧領域中,神經網絡(Neural Networks)的概念早在 1940 年代就被 Warren McCulloch 和 Walter Pitts 給提出了。然而要一直到 2010 年代,等 GPU 硬體發展成熟、網路的蓬勃發展累積了大量數據以後,神經網絡才得以發揮它的影響力。又或者是,Vannevar Bush 早在 1930 年代就在 As We May Think 這篇文章中提出了 Memex 這個打破書本的線性結構、由「關聯性」為基礎建立的資訊系統。然而要一直等到 1980 年代,個人電腦普及、資訊傳輸技術到位以後,人們才終於得以發展出以「超連結」為基礎的網際網路(World Wide Web)。

以上的例子揭示了一種我們可以做出卓越貢獻的方法:回顧那些由前人提出的重要想法,裡頭有哪些在當時難以實踐,但如今已經變得可行?這正是 Notion 和 Dynamicland 現在正在做的事。這也是跨領域知識為何重要的其中一個原因:歷史是多線交織的,拿計算機歷史中提出過重要想法的人為例,von Neumann、Norbert Weiner 和 Alan Turing 都是數學家、J.C.R. Licklider 是心理學家、Alan Kay 主修生物學、Steve Jobs 則是個商人。如果一個人只懂寫程式,眼中沒有來自其他領域的視角,就容易陷入主流思考的瓶頸,而看不到歷史整體的脈絡,更辨識不出那些重要的想法。

在獲得了這樣的領悟之後,我意識到:如果我想達成我的願景,我不只需要跨領域的知識,還必須關注歷史的洪流,搞清楚自己處在歷史中的什麼位置,才能知道我能如何順著這股洪流,加入我認為重要的元素,打造我所期望的未來世界。

目標

暸解到歷史和前人想法的重要性後,我開始花時間閱讀 J.C.R. Licklider、Douglas Engelbart、Alan Kay、Ted Nelson 等計算機先驅發表的一些早期文獻,以及 Bret Victor、Andy Matuschak、Michael Nielsen 等當代在朝類似方向努力的專家寫的文章和影片。其中影響我最深的,莫過於 Engelbart 在 1962 年發表的 Augmenting human intellect: A conceptual framework 這篇論文,以及他的官方網站裡的眾多影片和文章。令我感到訝異的是,我發現 Engelbart 的很多想法,其實我在過去三年期間都早已想過,又或是在各種不同的書和課程上接觸過。而 Engelbart 的論文用一種系統性的方式,把很多東西都連在一起了,這對我來說就好像給一個重度近視的人戴上眼鏡,世界瞬間變得無比清晰。而經由這樣的視角,Notion 和 Dynamicland 在做的事情也顯得更加合理。

當然,值得關注的、能強化人類智力活動的工具絕對不只 Notion 和 Dynamicland,還有 Roam、Muse、Figma、Are.na、Hypothes.is 等各種不同的產品。所以對我來說,除了搞清楚自己處在歷史中的什麼位置,辨識出那些在現代逐漸變得可行的重要想法以外,另一個重點則是去看看那些分散在世界各地的不同的人和計畫。這些人對這些想法做出了什麼樣的嘗試?獲得了什麼樣的成功?又面臨了什麼樣的困境?這些對我來說都是極為寶貴的資訊。

此時此刻,在「透過工具強化智力活動」這條道路上,我已經找到了我認為對人類世界極為重要的方向。我非常確定這是個值得我長期努力的方向,不只是因為它屬於「由前人所提出,在過去難以實踐,但如今已經變得可行」的想法,更重要的是,這件事情就算我不做,也必然會有人把它做出來。然而我覺得在這個方向上,其他人都沒有抓到重點,只有我才知道怎麼把它做對。我已經思考它三年了,我確信這個世界需要我來做這件事情。

我未來十年的目標,是打造一個真正普及世界的、我所重新設計過的開放超文本系統(Open Hyperdocument System),並以這個系統為基礎,建立新一代的網際網路。